- NAPOLEON: IN THE LAND OF THE PHARAOHES

Napoleon I and Vivant Denon dominated from the beginning archaeological exploration in Egypt. Emperors and barons, generals and artists – on a short journey they walked side by side and understood each other very well, even though essentially they had nothing in common. For one person, the pen is only used to sign military orders, give instructions, and make laws; the other used his pen to write easy, bawdy novels and create pencil drawings that are today among the most bizarre of all erotica.

On October 17, 1797, the Peace Treaty of Campo Formio was signed, ending the Italian campaign and allowing Napoleon to return to Paris. “Napoleon’s glorious days are over!” writer Stendhal said. He was wrong. In fact, the illustrious period of the great Corsican was just beginning. But before he swept Europe, he harbored a crazy, vain plan, sprung from a sick mind. Walking back and forth endlessly in a small room, withered by ambition, comparing himself with Alexander, no longer hoping for great works yet to be accomplished, Napoleon wrote: Paris weighs on me like a lead jacket! This Europe of ours is a molehill. Only in the East, where six hundred million inhabitants live, was it possible to establish vast empires and carry out great revolutions.”

On May 19, 1798, Napoleon set sail from Toulon with a fleet of 328 warships, carrying 38,000 men on board, almost equal to the force Alexander commanded when he launched his campaign in the East. Destination is Egypt.

The French plan was worthy of Alexander. Napoleon’s searching eyes darted across the Nile valley to the vast island of India. The goal of the initial crossing campaign was to deal a fatal blow to one of Britain’s main auxiliary forces, unfathomable in the European balance. Nelson, admiral of the British fleet, spent a month searching in vain throughout the Mediterranean, but could not trap Napoleon’s forces, although twice French warships were almost within sight.

On July 2, Napoleon stepped onto Egyptian soil. After the march in the hot desert, the soldiers happily bathed in the Nile River. On July 21 Cairo appeared before the eyes of French soldiers, a scene straight out of One Thousand and One Nights, with its 400 watchtowers and the massive dome of Jami-el-Azhar, the city’s central mosque. . In sharp contrast to the architecture lavishly decorated with gold and silver, felt against the pearly morning sky, there rising from the arid desert floor, silhouetted against the gray-purple Jebel Mokattam hillsides, was the figure silhouettes of giant stone structures, cold, heavy, and arrogant. It is the Pyramid of Gizeh, a petrified geometry, a silent eternity, symbols of a world that died long before the birth of Islam.

The soldiers did not have time to gape. All around them lie the vast ruins of a dead past, but Cairo, the symbol of an enchanting future, beckons. Between them and the glittering target was the army of the Mameluke generals . This colorful force consists of 10,000 battle-hardened cavalrymen, armed with glittering curved swords, mounted on the backs of diverse steeds. The commander was the ruler of Egypt, Maurad. Accompanying him were 23 governors. He mounted a white-feathered steed like a swan and led the army, his blue cloak sparkling with precious stones. Napoleon pointed at the pyramids. He exhorted his soldiers, as a general, a master of mass psychology, and as a European face to world history. “Soldiers,” he said loudly, “forty centuries are looking down upon you!”

The encounter was terrible. The strength of the Mamelukes cannot hope to compete with European bayonets. The battle turned into a bloody escape. On July 25 Napoleon entered Cairo, and half the march to India seemed to have been completed safely.

But on August 7, a naval battle occurred at Abukir. Nelson finally located the French fleet and massively attacked like an avenging angel. Napoleon was trapped. Abukir put an end to the Egyptian adventure, although it actually lasted another year. During this time General Desaix overran Upper Egypt, and Napoleon won a land battle at the same place of Abukir where his fleet was cut to pieces. Despite this victory, hardship, hunger, and disease tormented the French soldiers. A large number of soldiers were blinded by the Egyptian eye plague.

On August 19, 1799 Napoleon left his army behind. On August 25, from the warship Muiron , he watched the coast of the Pharaoh’s country sink into the sea behind him.

Napoleon’s expedition, foolish from a military point of view, had the long-term effect of awakening Egypt politically; but also launched scientific research into antiquity that continues to this day. Because Napoleon brought 175 “learned citizens” to Egypt. Soldiers and sailors call this complex of brain matter “donkeys.” The intellectuals brought with them a large library containing nearly every book on the land of the Nile that could be found in France, and dozens of crates of scientific instruments and measuring instruments.

The first time Napoleon showed himself to be interested in Egyptian culture was at a meeting organized by scientists, in the spring of 1798, in the large auditorium of the French Academy. While explaining the scientific tasks of the Egypt project, for emphasis he occasionally tapped his finger on the leather cover of Niebuhr’s Travels in Arabia that he held in his hand. A few days later astronomers, geometers, chemists, mineralogists, Orientalists, technicians, artists, and poets joined him in Toulon. And among them was an extraordinary man whom the Queen gallantly introduced as an illustrator.

Dominique Vivant Denon is his full name. During the reign of King Louis In St. Petersburg, he had served as embassy attache, and was also favored by Catherine, the Russian Empress. A man of the world, fond of women, amateur in all arts, good at speaking, and witty, Denon always manages to be friendly with everyone. When he was a diplomat working in the Swiss Confederation, he often visited Voltaire [ an outstanding French writer ], and painted the famous painting Breakfast at Ferney showing the writer eating breakfast in bed. . With the oil painting The Shepherd and the Baby Jesus painted in Rembrandt style, he was accepted into the Academy. News of the outbreak of the French Revolution reached him while he was living in Florence (Italy), where he was a familiar figure in the city’s art salons. He hurried back to Paris. From the independent and wealthy life of a diplomat and “ gentilhomme ordinaire ” [“ ordinary gentleman ”], he found himself suddenly on the list of immigrants. He witnessed his home and property being attacked.

Poor, abandoned, and betrayed everywhere, he wandered around in the shabby areas of Paris, making a meager living by selling his paintings. He wandered around the markets, witnessing too many heads rolling around in the Place de Grève, including the heads of some friends, until finally he found unexpected protection from Jacques Louis David, Great painter of the Revolution. He was given the job of engraving sketches of David’s clothes, which were destined to revolutionize French dress style. This work helped him gain the trust of the “indestructible man”. His property was soon returned, and his name was removed from the list of deportees. He had the opportunity to get to know the beautiful Queen Josephine and make an impression on Napoleon, and was allowed to accompany him on the Egyptian expedition.

He returned from the country of the Nile a respected and trusted person. He was appointed general director of all museums. As Napoleon continued to assert his power on the European battlefield, Denon followed him closely. He plundered works of art in the name of collecting, and he continued to do so until the first few bland paintings became some of the noblest decorations of France. Seeing how successful he was when drawing in color and pencil, he thought he could do the same in the field of literature. At a literary gathering, writers debated the issue of the impossibility of writing a realistic love story without using sex. Denon bets he can do it. Within 24 hours he completed Yesterday’s Score. This recent collection of stories has found him a place in the literary scene. Connoisseurs declare it an exquisite work of its kind. Balzac later called it “an educational book for married men, and gives young people a wonderful picture of the customs of the last century.”

Denon also wrote Oeuvre Priapique [ Sexual Paintings ], which appeared in 1793. This is a collection of acid etchings, and as the title suggests, they are brazenly sexual. It is also interesting in this regard to note that the archaeologists who have studied Denon seem to have been completely unaware of the erotic aspect of his activities. On the other hand, even a culturally knowledgeable historian like Eduard Fuchs, whose History of Moral Behavior devoted an entire section to pornography, was clearly unaware that Denon had played a role. important in the embryonic days of Egyptology.

This multi-dimensional and in some respects astonishing man clearly deserves to be remembered by posterity for a single feat. Napoleon conquered Egypt by bayonet, and lasted only a short year. And Denon conquered the land of the Pharaohs with his pencil and maintained it forever. It is through the power of eyes and skilled hands that Egypt once again comes to life in the consciousness of modern people.

From the moment he first felt the hot breath of the desert, Denon, the effeminate man of the sands, was suddenly aroused by a wave of fanatical enthusiasm for everything Egyptian. As he wandered from ruin to ruin, this enthusiasm did not wane.

He followed Desaix’s army, and with this general fiercely pursued Murad, the leader of the fleeing Mameluke army, through the desolation of Upper Egypt. At this time, Denon was 51 years old, old enough to be Desaix’s father. The general, as well as the officer ranks, favored Denon. As for the soldiers, they were surprised by someone who did not care about the extremes of the climate. One day he pushed his small old horse far ahead of the vanguard of the army, the rearguard still trailing behind. He left his tent at dawn and sketched on the march and in the barracks every night. Even when he was on a meager diet, he kept his painting notebook right next to him. One time, in the midst of the alarm, he suddenly found himself rushing into the middle of an ambush. When the soldiers counterattacked, Denon encouraged them to rush in by waving his drawing paper. Then, realizing that a scene worth recording was unfolding before his eyes, he forgot all about the artillery shells and engrossed in drawing.

Finally he encountered hieroglyphs. He was completely ignorant of them, and no one in Desaix’s army could satisfy his curiosity. Regardless, he just drew what he saw. And immediately, the keen, if not innate, eye distinguished three different types of pictograms. The hieroglyphs, he noticed, were either engraved in low relief, or in high relief. At Sakkara he sketched the Step Pyramid, and at Dendera the huge ruins of ancient Egypt. Tirelessly he hurried back and forth among the ruins that spread at Thebes with its 100 gates, and was disappointed when the order to disperse was given before he could grasp everything with his pen. Cursing furiously, he called some soldiers in his unit and told them to scrape off the dirt stains on the head of a statue that caught his attention. He continued to sketch while the army had long been on its way.

Desaix’s adventurous campaign took him as far as Aswan and the first waterfall of the Nile. At Elephantine, Denon painted the graceful columned chapel of Amenophis III. His masterful sketch is the only picture of the chapel that still exists, because in 1822 the structure was demolished. When the army returned home, after the victory at Sediman and the destruction of Murad, Baron Dominique Vivant Denon, with countless pencil drawings, brought back to France a lot of booty even greater than the wealth stolen by the soldiers. plundered from the Mameluke army. Denon’s sensibilities may have been ignited by the mystery of Egypt, but this excitement did not affect his precise drawing skills. His drawing style is realistic at the hands of an old sculptor who devotes all his energy to every detail, regardless of impressionism or expressionism, and calmly ignores the negative meaning. of the word painter. Denon’s pencil drawings became an invaluable source for contemporary archeology. They provided the basis for an aesthetically pleasing work in Egyptology, the first of its kind, the masterpiece Egyptian Description, in which science blossomed as a systematic intellectual endeavor.

Meanwhile in Cairo the Egyptian Institute was established. While Denon was busy drawing, the other artists and scientists of Napoleon’s working group measured, counted, researched, and collected whatever the ground of Egypt had to offer. Just on the ground, the material displayed before the eyes is suddenly so abundant that there is no longer any motivation to excavate. In addition to plaster models, masses of memorabilia of all kinds, manuscripts, paintings, and collections of animal, plant, and mineral specimens, Napoleon’s intellectual complex also brought home a few stone sarcophagi and 27 carved stone fragments, most of which are fragments of stone statues. Included among these is a polished black basalt stone stele, containing inscriptions in three languages. This heavy tablet became known as the Rosetta Stone, the key to unlocking the mysteries of Egypt.

But in September 1801, when Alexandria fell to the British, France had to surrender to the British all the lands in Upper Egypt they had conquered, and with them the expedition’s collection. about ancient Egypt. General Hutchinson undertook to transport them back to England. With the instructions of King George III, the items, which at that time were the most precious and rare, were stored at the British Museum. A year of French effort was successful, a year in which a number of scholars lost their eyesight because of the general situation. But then it was realized that, excluding the loss of the original to the British, all the specimens in the collection were closely copied. Thus, there is enough material to return to Paris for a generation of scholars to diligently study.

The first member of the expedition to use these items was Denon. In 1802 he published his wonderful work A Journey to Upper and Lower Egypt. At the same time, Francois Jomard began to compile his great work, based on the materials collected by the scientists in the group, and especially Denon’s massive amount of paintings. This masterpiece, a unique event in the history of archeology, immediately made an impression and attracted the attention of the modern world to a culture that until now had only been visited by a few tourists. history, a culture as remote and mysterious, if not completely hidden, as the culture of Troy.

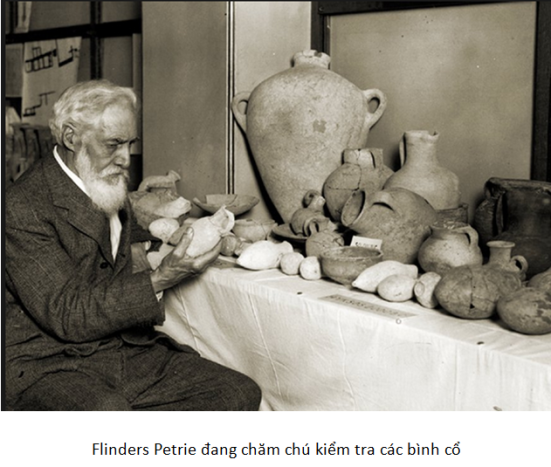

One of the first items of Egyptian art, called the “Narmer palette,” consists of a front and back. It is about 5,000 years old, and probably depicts Menes the Great himself, who founded the first dynasty, following his victory over enemies from Lower Egypt.

Jomard’s Description of Egypt was published over the four years from 1809 to 1813. The interest that the publication of these twenty-four volumes aroused was comparable only to the publication of Botta’s first work on Nineveh and Schliemann’s book on Troy.

In the age of the rotary printing press it is not easy to appreciate the significance of Jomard’s selection and compilation, with its many engravings, some colored, and high-class bookbinding techniques. The book series only came into the hands of the rich, and they kept it as a treasure of knowledge. Today, when every important scientific discovery is almost instantly disseminated around the world, the effect is multiplied millions of times through media such as photographs, movies, and sounds, excitement that the great discoveries caused have been greatly diluted. One work published on the heels of another, always competing for attention, contributes to a process in which each person knows a little about something, but doesn’t really know it. What’s profound? So it is not easy for modern people to understand what Jomard’s first readers felt when they picked up Description of Egypt . They saw in it things that had never been seen before, they read about wonderful new things, they became acquainted with a way of life whose existence had never before been suspected. More capable of appreciation than ourselves, these first readers must have experienced an overwhelming feeling of being transported thousands of years back.

Because Egypt is ancient, older than any other culture at that time. It was ancient when the political form of the future Roman Empire was being formed through meetings on the Capitoline Hill. It was ancient and decimated when Germanic and Celtic tribes in the northern European forests were still hunting bears. When the First Dynasty came to power, about 5,000 years ago, Egyptian history was shaped in the course of time, cultural forms evolved in the land of the Nile. And when the 26th Dynasty died, it took another 500 years to reach our era. During those 500 years, the Libyans ruled Egypt, then the Ethiopians, the Assyrians, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans – all of these events happened before the star shined on the Bethlehem cave, where Jesus was born.

Of course, the rocky wonders of the Nile were known to some, but their knowledge was more or less legendary. Only a few Egyptian monuments have been transported to museums in distant lands and shown to the public. During Napoleon’s time visitors in Rome could gape at the lion statues on the steps of the Capitol. He could also see the statues of some of the Ptolemaic kings – that is, later works, completed in the period when the splendor of ancient Egypt was being replaced by the new splendor of Egypt. Greece in Alexandria. Among the monuments truly representative of Egyptian antiquity in Rome are the 12 obelisks, plus some reliefs in the cardinals’ garden. Most commonly, Egyptian scarab jewelry was considered sacred by the people of the Nile. These scarabs were once used throughout Europe as a charm (see picture), and later as jewelry. That’s all.

And what little of what might be called scholarly material rich in authentic information can be found in the bookstores of Paris; But an excellent translation of Strabo’s five-volume set in 1805 made widely available authoritative treatises that had previously been within the reach of scholars. Strabo traveled throughout Egypt during the time of Roman Emperor Augustus. More valuable information is contained in the second book of Hetodotus, the great traveler of antiquity. But who reads Herodotus? How many people are familiar with the handful of even esoteric and scanty references to Egypt in ancient authors?

“Who covers himself with light instead of clothes,” said the poet. Early in the morning the sun rose in the cold blue sky, and sailed on its course, dazzling gold, scorching hot, reflecting on the desert the dark brown, vermilion, pale white hues. Shadows were as black as ink poured across the sand. And towards this place of endless sunlight, where there is no weather, no rain, no snow, no fog, and no hail, where the rumble of thunder is rarely heard or the flash of lightning is seen. – towards this desert, where the air dries to the bone, where no seed grows, where the land bears no fruit, crushed, fragile, brittle when clumped, rushing river The mighty Nile, father of all rivers, rushes in. The river rises from the far depths of the country and is fed by the lakes and tropical rains of remote Sudan. During the flood season, it overflows its banks, pours water into the sand, swallows the abandoned lands, and spews mud and silt in July. The river has done so for thousands of years, rising 52 feet (about 14 meters) each year. The symbol of this event is a group of stone statues in the Vatican in which there are statues of 16 children, each representing an En (a unit of length equal to 113 cm) of the flood level. When the flood receded, the Nile saturated the dry land and the hot sand. When the brown water layers have settled, green plants begin to sprout. Young seedlings appear, bringing double and quadruple harvests and bringing “years of plenty” to feed the people during “years of famine”. Every year a new Egypt rises, “a gift from the Nile,” as Herodotus described the event 2,500 years ago, the bread basket of antiquity. As far away as Rome, there was either famine or starvation, depending on the generosity of the Nile River.

In the towering cities rising from the sun-bleached landscapes people of different ethnicities and skin tones – Nubians, Berbers, Copts, Bedouins, Africans – crowded together through the narrow streets, shouting shout in different languages, welcoming a world of cool temples, pillared halls, and mausoleums.

In scenes of shadowless desolation the pyramids raise their heads. Sixty-seven pyramids stand in the wasteland around Cairo, arrayed around the “Rehearsals of the Sun,” monstrous tombs of kings. Just one of them required two and a half million blocks of stone to build, brought to the site by the strength of more than a hundred thousand slaves who worked hard for more than 20 years.

There the Sphinx of Gizeh lies crouched, the largest of its kind, half human, half lion. The lion’s mane was destroyed, its eyes and nose were only holes, because the Mameluke army used its head as a target to practice cannon shooting. But there it lay still for thousands of years, prostrate with its corpse and moon, a mass of stone so massive that Thotmes, dreaming of ascending the throne, found enough space to erect a stone between its feet. huge beer.

There are also towering pointed towers standing out against the crystal clear sky, standing guard over the temple gate, honoring the gods and kings. Some of these beautiful rock fingers point up to 91 feet (about 30 meters) into the sky. There are also stone tombs and mastaba mausoleums, statues of “local administrators” and statues of Pharaohs, stone sarcophagi, pillars and towers, reliefs and paintings. Those who once ruled this ancient kingdom enter eternity through frescoes, in rigid postures, breathing grandeur into every gesture, always depicted with a profile and aiming at a goal. some goal. “Egyptian life,” it was said, “is a journey into death.” The principle of salvation is so strongly emphasized in the wall reliefs that one modern cultural philosopher points out that “the road” is the most fundamental Egyptian symbol, with a meaning equal to “space”. ” of Europe and the “body” of Greece.

Practically every object in this vast cemetery of the past is covered in hieroglyphs. These hieroglyphs consist of signs, drawings, outlines, hints, all manner of mysterious and secret forms. The symbolism of this strange communication system draws inspiration from people, animals, plants, fruits, mechanical devices, clothing fabrics, utensils, weapons, geometric shapes, undulations and firelight. . Hieroglyphics are all over the walls of temples and burial chambers, on memorial stele, sarcophagi, stele, on statues of gods and mortals, on wooden boxes and ceramic vases. Even the pen holder and walking stick bear hieroglyphs. The Egyptians seem to like to write more than any other people. “If someone sat down to copy all the inscriptions in the temple of Edfu

The facade of the Temple of Edfu in Aswan

Jomard opened this magnificent world to Europeans who quickly awakened to the wonders of science and the wonders of the past. Thanks to Caroline, Napoleon’s sister, the excavation of Pompeii was promoted with renewed enthusiasm. Through Wickelmann, scholars learned the rudiments of archeology and enthusiastically began decoding the mysteries of antiquity.

It is true that the Description contains a wealth of drawings, copies, and descriptions, which the authors cannot explain, for that is beyond their powers. When, from time to time, they tried to guess, they were wrong. Because the relics arranged in books are themselves silent, and remain stubborn. Whatever order is imposed on them is purely intuitive, because no one has any idea how to interpret them concretely and empirically. Simple hieroglyphs were unreadable, as were hieratic and demonic scripts, which were simplified forms of hieroglyphs. 1 The written language is completely foreign to European eyes. The Description introduces a completely new world which, with respect to its internal relations, natural order and meaning, is a complete mystery.

In Jomard’s time, people wondered if there might be something missing that could solve the mystery of hieroglyphs. But is this possible? De Sacy, a great Orientalist, said that “the problem is too complicated and cannot be solved scientifically.” On the contrary, an unknown German teacher named Grotfend in Göttingen, wrote an article that correctly showed the way to deciphering the cuneiform script of Persepolis. His methods are showing results. And while Grotefend had little material to work with, there are now countless hieroglyphic inscriptions available to examine. Furthermore, one of Napoleon’s soldiers accidentally found a precious slab of black basalt. Even the first reporters to report on this find immediately knew that the Rosetta Stone was the key to solving the puzzle of Egyptian hieroglyphs. But who knows how to use this stone stele?

Not long after the discovery of the famous stele, an article about it appeared in the Egyptian Mail , published on the date of the Revolution: Fructidor month, 29th year of the 7th Republic . December name according to the French Revolution calendar: ND ]. By the rarest of coincidences, this Egyptian newspaper appeared in the parental home of the man who, twenty years later, in a unique work of genius, made the ability to read the inscriptions on the black stone stele and thus solve the problem of hieroglyphs

1 Demonic script is a simplified or popularized form of hieratic script, and hieratic script is in turn a shortened form of hieroglyphic script. Hieratic was used in secular or religious texts, until the word demonic appeared and became popular, and later hieratic was only for religious activities.

Napoleon Bonaparte and Vivant Denon

Denon’s Sphinx painting

The Nile River, the longest river in the world, is the god of Egypt

Djoser Step Pyramid in Saqqara

- CHAMPOLLION (I): THE MYSTERY OF THE ROSETTA STONE

When Dr. Franz Joseph Gall, a phrenologist, was traveling through France to promote the theory that the bumps on the skull could be used to determine a person’s personality. On this route, he surprised and ridiculed the people, sometimes he was honored, sometimes he was slandered. Then at a certain house in Paris he was introduced to a young student who immediately took an interest in him. According to professional habit he glanced at the young man’s head. He was stunned by its shape. “Oh,” he exclaimed, “what a linguistic genius!” Perhaps the doctor had already grasped information about the young man, because at that time this 16-year-old boy had mastered half a dozen Eastern languages as well as Latin and Greek.

Equally surprising is that Champollion’s birthplace is recorded in a fictional biography that was popular in the 19th century. Because there is no evidence to refute this colorful story, we are forced to It follows that this portrait of a controversial figure, to whom archeology owes much, must be presented.

In the small French town of Figeac, the wife of bookseller Jacques Champollion lay in bed, paralyzed, unable to move. Around the middle of 1790, after conventional doctors had given up and were unable to treat him, Jacques invited the wizard Jacqou to come. The town of Figeac happens to be located in the Dauphine region, in south-eastern France, and is known as the District of Seven Miracles. The Dauphine region is one of the most beautiful areas of the country, a place where God could be expected to come. The Dauphines are a conservative, stubborn people, not easily aroused out of their inertia, but once awakened, they can become fiercely fanatical. They are Catholic and believe in miracles and the occult.

According to the evidence of several sources, the magician Jacqou placed the seriously ill woman on a layer of heated medicinal plants, and made her drink hot wine. He said, if she followed his instructions, she would quickly heal.

Furthermore, to the surprise of her family, he predicted that she would give birth to a son, now in her womb, who would later be famous and remembered for centuries.

On the third day the woman became seriously ill and sat up and got out of bed. On December 23, 1790, at two o’clock in the morning, Jean Francois Champollion was born, destined to decipher hieroglyphs.

If, according to rumor, the devil’s females have two-toed feet, it is not surprising to find scant signs of the prenatal influence predicted by the magician. Upon examining the baby, the family discovered that its corneas were yellow, a common characteristic of Eastern peoples and obviously most unusual for Western Europeans. Furthermore, it had skin that was almost tanned, and its face was definitely Oriental. Twenty years later, everyone knew him under the nickname “the Egyptian.”

Jean-Francois Champollion was a son of the French Revolution. The Republic was proclaimed at Figeac in September 1792. From April 1793 was the reign of Terror. Champollion’s family lived in a house just thirty steps from the Place d’Armes – a square later named after the boy – where the pillar of liberty was erected. The sounds that Jean-Francois remembers hearing were the loud music of the popular Carmagnole song and the wailing of refugees seeking safety from the agitated mob in his father’s house, in There was a monk who was his first tutor.

At the age of five, Jean-Francois, according to one admiring biographer, achieved his first decoding feat: he figured out how to read by comparing lists of words he had memorized. with written text. It was only when she was seven that she first heard the mysterious name Egypt, a name that to a sensitive child was reminiscent of mysterious hallucinations; As for his brother, 12 years older than him, Jean-Jacques, was the hope of accompanying Napoleon’s expedition to the ancient land of Egypt, but then it was shattered at the last minute.

Young Champollion, according to rumors as well as recorded evidence, did not study well while at Figeac. To save this situation, the older brother, now a talented grammarian with great interest in archaeology, in 1801 took his younger brother to Grenoble and paid for his younger brother’s education. When at the age of 11 Francois quickly showed a rare talent in Latin and Greek, and began to devote himself to the study of Hebrew with astonishing success, his brother immediately decided to hide his own talent. so that my younger brother’s talent can shine more brightly. From this moment on he called himself Champollion-Figeac, then just Figeac. The younger brother’s humility and belief in a bright future is truly precious when remembering that he himself already has some reputation.

That same year, Jean-Baptise Fourier, a famous mathematician and physicist, had a conversation with a child with many talents in languages. Fouriet accompanied the Egyptian expedition and later served as secretary at the Egyptian Institute in Cairo. He was also commissioned by the French military government in Egypt as chief of jurisdiction and was a leading proponent on the scientific committee. At this time he was the prefect of Isere and lived in the capital Grenoble, where he quickly gathered a number of talented intellectuals. During a school inspection visit, he had the opportunity to debate with Francois and was impressed with the young student’s outstanding intelligence. He then invited him to his house and showed off his Egyptian collection. The dark-skinned young man immediately fell in love with the papyrus scrolls and hieroglyphic inscriptions on stone tablets that he saw for the first time. “Has anyone read these words yet?” he asked. Fourier shook his head. “I will do it,” Champollion declared with strong confidence. “In a few years you can do it. When you grow up.” Years later he often mentioned this event.

This anecdote immediately reminds us of another young man who confided to his father: “I will find Troy.” Both expressed an iron faith, a wild certainty. Yet their two youthful dreams were realized in two different ways. While Schliemann remained an autodidact throughout his life; Champollion never deviated an inch from the official educational path, even though his knowledge developed at a speed that soon left his classmates far behind. While Schliemann began his work without any technical tools, Champollion equipped himself with virtually every understanding the century could offer.

The older brother supervises my studies. He tried to control his crazy hunger for knowledge, but failed. Champollion explores every nook and cranny of knowledge, jumping from peak to peak. At the age of 12 he wrote his first book, Tales of Famous Dogs. Realizing that his historical research was hampered by the lack of organized journals, he created his own chronicle which he called “Chronicles from Adam to Champollion the Younger. ” When the eldest brother stepped back to let the light of glory shine only on Jean-Francois, the boy responded to the praise by calling himself “Young Champollion”, to remind everyone that there was another Champollion. you follow.

When he was 13 he began to learn Arabic, Syrian, Chaldean, and finally Coptic. In this respect, it was surprising that everything he learned or did, and indeed everything that happened to fall into his hands without having sought it, was somehow related to the subject of Egypt. Whatever problem he set out to solve seemed to lead him to some problem about Egypt. He used Ancient Chinese to find a connection between that language and Ancient Egyptian. He studied text excerpts from the Zend, Pahlavi, and Parsi languages – rare linguistic documents stored in Grenoble that were only allowed to be used thanks to Fourier’s intervention. Using every source he could get his hands on, in the summer of 1807, at the age of 17, Champollion drew the first historical map of the Pharaoh’s dynasty.

This bold effort is worthy of appreciation when one considers that he had no other sources of reference other than the Bible, truncated texts of the Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew languages, and manuscripts. contrast with Coptic, the only language that provides a link with Ancient Egyptian. Coptic was actually spoken in Upper Egypt until the 17th century.

Knowing that Champollion wanted to send his research to Paris, the high school faculty asked him to write about a topic of his own choosing. They wait to receive a normal high school essay; Instead Champollion presented an entire outline for an entire book titled: Egypt under the Pharaohs.

In September 1807 he read the introduction to this proposed project. The entire school’s teaching staff gathered to listen to this slender student’s presentation. He stood before them straight and serious, his face glowing with the vibrant beauty of a prodigy. His ideas flow through a series of bold topics, driven by strong arguments. The professors were so shocked that they elected him to join the teaching council on the spot. Renauldon, the school principal, stood up and hugged Champollion. “When we agreed to choose you as a member of the teaching staff, we recognized your achievements up to this moment,” he said. “But more than that, we look forward to what you will do in the future. We are all confident that you will justify our expectations, and when you have made a name for yourself, do not forget those who first recognized your genius.”

And overnight Champollion jumped from the position of student to the position of teacher.

Leaving school, Champollion was ecstatic with joy. At this time he was a sentimental teenager, an intense personality prone to sad moods. In many fields he was recognized as a genius, and his early intellectual development was well known. Physically, he is also old before his time. (For example, when he decided to get married right out of high school, it wasn’t a case of puppy love at all.) He knew he was entering a new phase of his career. He dreamed of Paris, the capital of light, the center of all Europe, the epicenter of politics and intellectual adventures.

By the time the heavy carriage carrying the two Champollion brothers had traveled more than 70 hours and was approaching Paris, Champollion was completely immersed in the jubilant scene, suspended between reality and dream. Yellow papyrus scrolls floated before his eyes, voices from dozens of different languages whispered in his ears. He thought about the Rosetta Stone, a copy of which he had seen with Fourier’s permission. The hieroglyphs carved deep into the basalt rock haunted fragmented and chasing thoughts.

According to a reliable source, it is said that on this journey of the two brothers to Paris, Champollion suddenly had secret ideas. He confided to his brother his plans, and now suddenly knew that the fulfillment of this hope was firmly within his reach. His dark eyes sparkled on his dim face as he said: “I will decode the hieroglyphs. I know I can do it.”

A man named Dhautpoul is credited with discovering the Rosetta Stone. Other sources claim that it was Bouchard, but a closer investigation revealed that Bouchard was just an official in direct control of a group of workers working at the Rachid Fort ruins; he himself could not find the rock. This fort – which the French renamed Fort Julien – was located four or five miles northwest of Rosetta, on the banks of the Nile. This same Bouchard was responsible for carrying the stone back to Cairo.

The Rosetta Stone was actually dug up by an unknown soldier. It can be inferred that he was also an educated person, or at least had enough sense to recognize the rarity and value of lithographs. It is also possible that he was so ignorant and superstitious that he mistook the inscriptions on the stone stele for a witch’s spell, causing him to be so frantic that it attracted Bouchard’s attention to the artifact.

Rosetta stone is about the size of a table top, about 115 cm long, 72 cm wide and about 28 cm thick. It is made of polished basalt stone that cannot be broken when hammered. On one shiny surface are three columns of writing, partially eroded by two thousand years of sand and dust. The first column, consisting of 14 rows, are hieroglyphs; The second column, 32 rows, is written in demonic characters and the third column, 54 rows, is written in Greek.

Greek! So it can be read and understood.

A general of Napoleon’s, with a Greek bent, immediately undertook to translate the Greek column. He found that the encyclical recorded a directive from the Egyptian clergy, issued in 196 BC, praising Ptolemy Epiphanus for the benefits he brought.

Along with other trophies, the stele, after the fall of Alexandra, fell into British hands and was brought to the London Museum. Fortunately, before handing it over, the French copied the text in plaster, along with all the other antiquities. These copies were brought back to Paris. The scholars gathered around and began to compare.

The arrangement of the text shows that the three columns have the same meaning written in three languages. The Egyptian Journal of Letters suggests that this is the key to unlocking the gates to the dead kingdom, an ability to “interpret Egypt through the Egyptian language.” Once the Greek inscriptions were translated, there would no longer be much difficulty in bridging the gap between hieroglyphs and Greek writing.

The most brilliant minds of the day took up the challenge, in England (using the original Rosetta Stone) and also in Germany, Italy, and France. But no results. One and all make wrong assumptions. Their mistake was to read the hieroglyphs partly according to Herodotus’ subjective ideas. This is one of the typical misconceptions that has persisted throughout the historical development of humanity. To delve deeper into the mystery of Egyptian writing, it is necessary to radically change Copernicus’ viewpoint [when he considered the sun to be the center of the solar system, not the earth as was the view of ancient times and of America. church], it takes an explosive inspiration to break all barriers of tradition].

The older brother, Champollion-Figeac, had a former teacher named de Sacy who lived in Paris. De Sacy, despite his scruffy appearance, was a scholar of international reputation. When Figeac brought his younger brother, now 17 years old, to meet de Sacy, he behaved as if he were an equal. In fact, he treated de Sacy as he had treated Fourier when he first met this famous man in Grenoble some six years ago.

De Sacy seemed a bit skeptical of the prodigy from the provinces. Already at the age of 49, and the intellectual leader of his time, at first he did not know what to do with this young man, whom, in his article Egypt under the Pharaohs, he wrote. Just looking at the introduction, I envisioned a project that even the author himself admitted would not be completed in his time. Yet much later, recalling his first meeting with Champollion, de Sacy said that the young man made “a deep impression” on him. And no wonder! The above book was almost completed by the end of the year that the two met. The 17-year-old young man took advantage of the publicity that he would receive seven years later after the book was published.

Champollion threw himself into research. Completely alienated from the pleasures of Paris, he buried himself in libraries, running from academy to academy, learning Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian – “the Italian language of the East,” according to as de Sacy aptly calls it. In short, he immersed himself in all the Oriental languages, laying the foundation for a thorough understanding of their peculiar developments. Meanwhile, he wrote to his brother asking him to get him a Chinese grammar book, “just for fun,” as he said.

He has such a thorough understanding of Arabic that his pronunciation is really perfect. At a meeting, an Arab greeted him in a salamm style , thinking he was a member of his race. Just through books, he acquired such a thorough knowledge of Egypt that the famous African traveler Somini de Manencort, after a conversation with the young man, exclaimed: “He knows everything about Egypt.” The country we exchange is no less than me!”

Just a year later he was speaking and writing Coptic so fluently that – “I speak Coptic for myself,” he said – for practice he wrote a diary in Coptic. This strange incident, forty years later, caused a famous irony. A French scientist mistook these records for Egyptian originals from the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus and wrote a commentary on them. This is similar to Professor Duc Beringer solemnly declaring that some of the bones that the students in Wurzburd staged as a joke were ancient fossils.

While living in Paris, Champollion encountered many hardships. Without his brother’s generosity and devoted care, he would have truly starved to death. He lived in a cramped, shabby room near the Louvre Museum, with a rent of 18 francs a month. He couldn’t even earn that small amount of money. He wrote a letter to beg his brother, lamenting that he was at his wit’s end. He couldn’t even make ends meet. His brother replied that he would probably have to mortgage his library unless Francois cut costs. Cut back? Cut more? His shoes were worn out and his shirt was tattered. The situation was so bad that he was embarrassed to show his face on the street. The winter was unusually harsh and he fell ill. As he lay buried in the cold, damp room, the germ of the disease was planted, the disease that would eventually take his life. If it weren’t for those two small achievements, he would have completely collapsed from despair.

As if to compound his plight, the Emperor needed more soldiers and in 1808 issued an order to mobilize all young men over 16 years old. Champollian panicked. His weak personality could not handle physical exertion. Despite his ability to pursue the grimmest intellectual pursuits, he shuddered as he watched the parade of guards, pawns in a machine that leveled all individual differences. Didn’t Winckelmann suffer when the army threatened to swallow him up? “There are days,” Francois wrote to Figeac sadly, “when I almost go crazy.”

My brother, ready to lend a helping hand as ever, overcame many obstacles to protect Champollion. He enlisted the help of friends, drafted petitions, and wrote countless letters. As a result, Champollion was finally able to continue researching dead languages during the chaos of war.

Another matter that had once occupied his mind, which now began to fascinate him, making him sometimes forget the threat of being recruited into the army, was the study of the Rosetta Stone. In this respect he resembled Schliemann, who postponed learning Greek until he had taught himself to speak and write all the other European languages. As Schliemann is with the Greek, so is Champollion with the Rosetta Stone. Although the young man’s thoughts always returned to the mysterious stone, until now, he still hesitated, knowing that he was not equipped with enough knowledge to completely solve that decisive problem. .

However, now, after seeing a copy of the Rosetta Stone made in England, he suddenly couldn’t completely restrain himself any longer. But he restrained himself from comparing the stone block with some paper text instead of diving into the actual decoding. His first attempt at stele enabled him to “independently find the correct values for an entire line of words.” “I send you the first stage for your consideration,” he wrote to his brother on August 30, 1808. At that time he was only 18 years old. For the first time one could sense the young discoverer’s pride peeking out beneath the typically humble explanation of his method.

While he had taken the first steps, and knew that he was on the right track on the path to success and fame, regardless of hardships and criticism, he suddenly received news that shocked him. . The news threatened to destroy the elaborate preparations and the hope that was taking hold: the hieroglyphs had been deciphered.

After a moment of shock, he regained his composure. He walked through the street toward the College de France, and bumped into the friend who had sent him the news, news that he had not expected to make him weak. Champollion’s face turned pale and he staggered, having to hold on to his friend to keep from collapsing. Everything he lived for, thought about, and suffered for was gone with smoke.

“It’s Alexandre Lenoir,” the friend said, “His book has just been released, it’s just a thin volume. He titled it New Interpretation. In it he deciphered all the hieroglyphs. Think about what that means!”

Yes, think about what that means!

“Lenoir?” Champollion asked. He shook his head, his eyes shining with hope.

Just yesterday he met Lenoir. You’ve known him for about six months. Lenoir was a capable scholar, but far from a genius. “No way,” Champollion said. “No one told me anything about decoding. Not even Lenoir himself mentioned it.”

“Does that surprise you? With such a great discovery, who wouldn’t keep their mouth shut?

Champollion suddenly stepped back. “Where is the bookstore?” he asked. Then he hung his sausage around his neck and ran. With trembling hands, he counted the money displayed on the dusty counter. Lenoir’s pamphlet was bought by very few people. Then he quickly ran back to his room, collapsed on the couch, and began reading. . .

In the kitchen, the landlady Mecran was placing a pan on the kitchen counter. She was suddenly startled when she heard a terrifying scream coming from the room. She listened for a moment in terror, then rushed to the door and looked in. Francois Champollion was lying on the sofa, his whole body vibrating. He was laughing and laughing, each time frantically.

You have Lenoir’s work in your hands. Decoding hieroglyphs? The flag of victory was raised too soon! Lenoir’s book is all nonsense, haphazardly fabricated, a fanciful mixture of imagination and misguided erudition. Champollion is qualified to realize this.

It was true that the punch of information was terrible, and Champollion never forgot that feeling. His panicked reaction shows how he fell into the problem of raising the voices of those dead symbols. That night, when he was exhausted and fell asleep, he had wild dreams. He heard Egyptian voices speaking from the illusion. In the dream, his true self appeared clearly, unencumbered by the press and daily entertainment, revealing a person haunted, crazy, bewitched by hieroglyphs. His dreams were woven with omens of triumph. Yet there were still a decade separating him from that destination.

The Rosetta Stone is the key to decoding hieroglyphs

Champollion, the man who makes stones talk

- CHAMPOLLION (II): Treason and Hieroglyphs

At age 12, while reading the Old Testament in the original, Champollion wrote an essay arguing that a republic was the only reasonable form of government. Growing up amid the innovative imaginations that paved the way for the century of enlightenment and the liberation of the powers of the French Revolution, he felt the pain of living under the shadow of a returning dictatorship, at first sneaking in with hints. examples, decrees and finally revealed their true colors after Napoleon was crowned Emperor. Unlike his brother, Champollion was not captivated by Napoleon’s charm.

At that time it was the Egyptologist Champollion who, motivated by the call of freedom, attacked the Bourbon stronghold [the last king before the Revolution] in Grenoble, waving his flag high. He tore down the imperial flag standing on the citadel tower, and replaced it with the tricolor flag of the Revolution, the flag that had flown for a decade and a half before Bonaparte’s legions swept across Europe.

Once again Champollion returned to Grenoble. He was appointed as a history teacher at the university from July 10, 1809. At the age of 19, he was teaching young students, many of whom had worked with him in high school just two years before. It was completely understandable that he had many enemies. Almost immediately he finds himself trapped in a web of intrigue spun by older professors whom he easily outsmarted and unintentionally insulted.

And what strange new ideas the young history professor fights for! He fiercely defended the view that truth is the highest ideal in historical research, which means an absolute truth, not the Bonaparte or Bourbon version. To achieve this ideal he demanded freedom of imagination, at a time when inquiries of all kinds were prohibited and restricted by political control tools. Historians, he felt, should not pay attention to the powers that be. He demanded the continued exercise of freedoms that had been shouted from the rooftops in the early days of revolutionary fervor, but were now constantly betrayed. Champollion’s political campaign inevitably caused him conflicts with those of his time. He never deviated from his convictions, although he often felt discouraged. At times like that, he told his brother an idea that could have been taken from Voltaire’s Candide [a French writer with revolutionary views], but which he, an Orientalist, liked to quote from a saint. more Eastern letters. “Make your land grow crops! In Zend-Avesta * taught: Turning six acres of fallow land into cultivation is better than winning 24 battles. My opinion is the same.” More and more stuck in an academic world filled with intrigue, with low morale and a salary cut by up to a quarter through professional tricks, he wrote: “Your fate has been decided. I must be as poor as Diogenes [a cynical Greek philosopher, founder of the Cynic school, lived in the 4th century BC, despised material things and the comforts of life, worshiped nature. : ND]. I probably have to buy a box to live in and a sack to sleep in [like Diogenes]. Maybe then I can hope to survive thanks to the famous generosity of the people of Athens [where Diogenes resided].

He wrote satirical articles on Napoleon. What’s more, when Napoleon finally lost all power, and when, on April 19, 1814, Allied troops entered Grenoble, Champollion wondered bitterly whether a rule of law could now really replace government. Bonaparte’s tyranny or not and saw that there was little hope of it.

His concern for the freedom of government and science did not dampen his enthusiasm for Egyptology. His hard work reaped incredible results, even though he divided his time among too many unfamiliar and sometimes unimportant topics. He compiled a Coptic dictionary for his own use, and at the same time wrote plays to perform at cultural gatherings in Grenoble. In the French tradition that began with Peter Abelard in the 12th century he composed political songs, which were sung in the streets as soon as they were completed. He also continued his main work, which was to dig deeper and deeper into the mysterious world of Egypt. Ignore the screams in the streets, “ Vive l’Empereur !” [ Long Live the Emperor, referring to Napoleon] or “ Vive le Roi! [ Long Live the King, referring to the Bourbon dynasty before the Revolution ], his mind was never separated from this main concern. He wrote countless essays, he composed outlines for the work he would write, and was devoted to anyone who came to ask for help in writing.

- The code of Zoroastrianism, a popular religion in Persia, was born 1,000 years BC, and was destroyed by Islam in the 9th century, with Zoroaster as its leader, and had a profound influence on Judaism, Christianity and Islam have many precepts such as: monotheism, no idolatry, belief in the Last Day when people will be judged to go to heaven or hell. . .]

my dissertations, trying to understand the needs of mediocre students. Too much work wore out his nerves and health. In December 1816 he wrote: “Every day your Coptic dictionary grows thicker, and its author becomes thinner.” He groaned when he saw that he had written page 1069 and the project was still not finished.

Then came the 100 Days War [marking the time from which Napoleon escaped from the prison island of Elba until the day he was captured by the Allied forces, ending his fate], when Europe once again groaned under Napoleon’s iron hand. . Overnight the executed became the executioner, the ruler became a subject, the king became a refugee. Champollion himself was too excited to do anything. “Napoleon is back!” The saying is on everyone’s lips. The reaction of the Paris press was truly brazen drama. Big headlines running across newspapers, landmarks of deceit, reflect attitudes that have turned as discolored as a chameleon’s skin. “The Beast Has Escaped” gradually evolved into: “The Werewolf Has Landed in Cannes”; “The Dictator Is in Lyon”; “The Usurper 60 Hours from the Capital”; “Bonaparte Is Coming With Speed”; “Tomorrow Napoleon will enter the capital”; and finally “His Majesty Is at Fontainebleau.”

On March 7 Napoleon entered Grenoble, leading his army. Using a cigarette box to knock on the city gate, the torchlight illuminated his face. Very aware of his tragic role in this historical scene, in one spine-chilling moment, Napoleon alone raised his chest to welcome the cannon pointed at him from the top of the wall. From above, the gunners ran in confusion. Then the cry rang out in the sky: “Long live the Emperor!”, then the “adventurer” entered, and when he came out he was an emperor.” For Grenoble, the heart of the Dauphine, was the most important operating point that had to be won on Napoleon’s triumphant return route.

Figeac, Champollion’s brother, had in the past openly expressed his sympathy for Napoleonic doctrine. Now his enthusiasm has exceeded the limit. When Napoleon requested a capable private secretary, the mayor brought Figeac. He was a bit hesitant, so he called his name “Champoleon.” “What a good omen!” The Emperor exclaimed. “This guy has half my name!” Champollion was also present when the Emperor interviewed his brother. Napoleon inquired about the young professor’s work and was told about the Coptic dictionary and grammar. The Emperor was very impressed by this young scholar. He talked with Champollion for a long time. He promised him help to publish Coptic works in Paris. Still not satisfied, the next day the Emperor visited Champollion at the university library, where they discussed the young professor’s language research again.

The two Egyptian conquerors stood facing each other. One person has included the land of the Nile River in a plan to conquer the world and hopes to revive that country’s economy with a massive irrigation system. The other had never set foot on Egyptian soil, but with the eyes of wisdom he had seen the ancient ruins a thousand times, and was finally able to revive them by the power of knowledge alone. Napoleon’s imperial imagination was so buoyed by his encounter with Champollion that he announced on the spot his decision to adopt Coptic as the official Egyptian language.

But Napoleon’s fate was numbered day by day. His downfall was as tragically sudden as his recent escape. Elba was a place of exile; and now St. Helena will be a grave.

Once again the Bourbon dynasty returned to Paris. They lack determination, and their revenge is relatively mild. But it is still inevitable that hundreds of death sentences will be announced. “Punishment falls like nectar upon the Jews,” people said at the time. Figeac was among those chosen for revenge, because he had exposed himself when he accompanied Napoleon to Paris. In the political measures immediately initiated against Figeac, no distinction was drawn between him and Champollion, an error which the malicious enviers of the young professor at Grenoble did not bother to correct. To make matters worse, Champollion, in the final moments of the 100 Day War, unwisely helped found the Delphinatic League, a program to promote freedom in all areas. Of course this program has now become highly suspect. Champollion made a serious tactical mistake when he attempted, unsuccessfully, to raise 1,000 francs to buy an Egyptian papyrus.

When the royalists approached Grenoble, Champollion presented himself at the city wall, asking to volunteer to defend, completely unaware of which side gave more freedom. But what happened? Just as General Latour began shelling the city, possibly causing damage to Champollion’s priceless manuscripts, the young man hastily climbed down the city wall, forgetting about politics and war, and ran as fast as he could to the upper floors. three of the library. There he hid throughout the bombardment, carrying water and sand to put out the fire, alone in the large building, risking his life to save his papyrus scrolls.

Only after being fired from university for treasonous activities was Champollion finally able to truly return to his work of decoding hieroglyphs. The dismissal lasted a year and a half, followed by hard labor in Paris and Grenoble. Then a new indictment charging treason sounded like it was about to be released. In July 1821 he escaped from the city in which he had risen from student to professor. A year later he published his famous work Letter to Monsieur Dacier on the Problem of the Alphabet of Phonetic Hieroglyphs . This monograph outlines the basics of successful decoding, and causes heated discussion among those interested in solving the mystery of Egyptian pyramids and temples.

A number of ancient authors mentioned hieroglyphs, and during the Middle Ages a number of odd interpretations of them appeared. Herodotus, Strabo, and Diodorus, all of whom traveled throughout Egypt, believed that hieroglyphs were incomprehensible pictorial writing. Horapollon, in the 4th century BC, left behind a description of Egyptian writing. (referring to the implausibility of the writings about Egypt by Clement of Alexandria and Porphyry [two prominent Greek philosophers in the early centuries AD].) Horapollon’s comments are often used as a starting point for later authors for lack of any better source on which to base their argument. And Horopollon believed that hieroglyphs were a way of writing in pictures. Based on this point of view, throughout the following centuries the overwhelming tendency was to search for a purely symbolic meaning for those images. This tradition allows laymen to arbitrarily imagine their meanings, driving scholars crazy.

It was only when Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs that we realized how wrong Horopollion was. Egyptian writing actually evolved far beyond its original symbolism, in which the three zigzags symbolized water, floor plans symbolized houses, flags symbolized gods, and so on. This interpretation of allusions, when applied to later inscriptions, leads to serious misunderstandings, some of which are sometimes absurd.

Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit monk, is famous for creating the magic lamp [a type of projection using a lens and lamp, to project drawings on the wall, created in the mid-17th century], between 1650 and 1654 published in Rome four books containing “translations” of hieroglyphs, none of which even remotely matched the original text. For example, the group of symbols representing the word autocrator , which was a title for the Roman emperor, in Kircher’s reading means: “Osiris is the creator of all fruit and good harvests.” ; through the power of fertility that Holy Mopta took from heaven and brought it down to his domain.” Despite this momentous error, Kircher at least foresaw Champollion and others in recognizing the value of studying Coptic, the oldest form of the Greek language – a value that dozens of scholars fake protest.

One hundred years later de Guignes, before the members of the Paris Institute of Inscriptions, published a theory, based on a comparison of hieroglyphic systems, that the Chinese were colonists of Egypt. Yet nearly every error of this kind contains within it some germ of truth. De Guignes, for example, correctly read the name of the Egyptian King “Menes,” which a rival changed to “Manouph.” Voltaire, the most bitter critic of that time, then turned to attack the etymologists, “those who despise vowels and underestimate consonants.” British students of the same period, reversing the thesis mentioned previously, declared that the Egyptians originated from China!

We might think that the discovery of the Rosetta Stone would end the wave of indulgent speculation, but it seems the opposite has happened. The solution to this problem now seems so obvious that even amateurs are starting to play the game. An anonymous contributor from Dresden reads the entire Greek text word for word into equivalent hieroglyphic fragments on the Rosetta Stone. An Arab named Ahmed ibn Abubekr “lifted the veil” covering the text that an earnest Orientalist named Hammer-Purgstall had been unable to translate. An anonymous Parisian said he recognized the 100th Psalm in a temple inscription found in Dendera. At Geneva appeared a translation of the inscription found on the “Pamphylitic obelisk,” said to be a report of the victory of good over evil 4,000 years ago from Christ.”

One oddity after another. Imagination combined with remarkable arrogance and stupidity belongs to Count Palin, who declared that he recognized the meaning of the Rosetta Stone at first sight. Relying on Horapollon, on Pythagorean doctrine, and on magical powers, in just one night the Count achieved perfect results. Eight days later he presented his interpretation to the public, claiming that the speed of his breakthrough had “preserved him from the mistakes that inevitably arise from too much contemplation.”

Champollion sat motionless in the middle of this fireworks display, patiently arranging, comparing, testing, slowly climbing the long steep hill. Meanwhile a didactic volume from the hands of Abbot Tandeau de St. Nicolas told him that hieroglyphs were not a writing system at all, but just a type of decoration. Undeterred, as early as 1815, in a letter discussing the subject of Horopollon: “This work is called Hieroglyphica, but it does not contain an interpretation of what we understand to be hieroglyphs, but rather symbols Sacred carvings – that is, Egyptian symbols – were quite different from actual hieroglyphs. My view runs contrary to popular opinion, but the evidence I cite for this view is found on Egyptian obelisks. The sacred carvings clearly show the symbolic landscapes mentioned by Horapollon, such as the snake biting the swan, the eagle in a characteristic pose, the ethereal rain, the headless man, the dove with laurel branches, etc., but there is nothing symbolic in the actual hieroglyphic writing.”

Detail of the Narmer Tablet, late fourth millennium BC Horus the Eagle symbolizes the king, holding in his hands a conquered land (represented by an oval with the head of a bearded man) pulled by a string rope – refers to submission. The conqueror stood on six blooming lotuses. The blooming lotus is the symbol for 1,000, so this picture shows 6,000 prisoners. The harpoon below certainly indicates the name of the country. The square is filled with zigzags that could indicate that the country is located on the coast. Both symbols certainly point to Syria.

During these years, hieroglyphics became an overarching concept of a mystical Epicureanism*. All sorts of mystical, astrological, and fruitarian doctrines are attributed to them, even agricultural, commercial, and administrative implications for practical life. Biblical quotations are also found in it, even antediluvian legends, not to mention Chaldean, Hebrew, and Chinese excerpts. “It was as if the Egyptians,” Champollion observed, “had nothing to express in their own language.”

All attacks against this target of interpretation are more or less based on Horopollion. There is only one way to decode, which is the way away from Horapollon. That is the direction Champollion has chosen.

Great intellectual discoveries rarely have an exact date of birth. They are the result of constant exploration in a long process of focusing the mind on a single problem. They represent the intersection of the conscious and the unconscious, of purposeful observation and wandering daydreaming. Rarely is a solution achieved overnight.

Great inventions lose their charm when dissected in the light of the hunt. In retrospect, to those who have understood the principle involved, the mistakes must have seemed somewhat comical, the wrong views committed were the result of blatant blindness, and the problems were simple. single. Today it is difficult to imagine Champollion daring to recklessly oppose the Horapollon tradition. It must be remembered that both the experts and the informed public adhered to Horapollon for two weighty reasons: First, Horapollon was revered as an authority in ancient times, in the same spirit that the central thinkers The ancients revered Aristotle, and as later theologians revered the early church fathers. Second, even though they were skeptical themselves, they simply could not see hieroglyphs as anything more than symbols, conventionalized images. Even the evidence of the eyes supports this argument. Moreover, Horapollon lived a millennium and a half closer to the end of hieroglyphics, and this advantage seems to tip the balance in favor of his view, which affirms what everyone can be seen and touched – pictures, pictures, and more pictures.

- Epicureanism, founded by Greek philosophers in the early 4th century BC, advocated that the goal of life is to enjoy noble pleasures. To achieve that, people must live simply, acquire human knowledge, and limit desires. This will lead to peace, no more fear, no more physical suffering, this is the noblest human happiness.

We cannot say exactly when this happened, but the moment it occurred to Champollion that the pictures in hieroglyphs were “letters” (or, more precisely, “phonetic symbols” – stated

His original code was: “not purely alphabetic, but also phonetic”) he passed a decisive turn away from Horapollon, and followed the correct route to finally succeed in decoding. Can we talk about inspiration after so many years of hard work? Is this a joyful moment of complete breakthrough? The truth is that when Champollion first toyed with the idea of phonetic hieroglyphics, he was firmly against it. He even identified the sign of the horned serpent with the letter f and then erroneously resisted the idea of a complete phonetic system. Other investigators, among them the Scandinavians Zoega and Akerblad, the Frenchman de Sacy, and, above all, the Englishman Thomas Young, all recognized that the demotic inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone were “alphabetic writing.” “, and, like that, partially completed the solution of the problem. But they cannot go beyond this point. They either give up or come back. De Sacy declared his complete surrender. The hieroglyphs, he said, continued to be “the inviolable * Ark. ”

Even Thomas Young, who achieved outstanding results in deciphering the demonic inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone, for the reason that he read it phonetically, adapted his own theory in 1818. In deciphering Ptolemy ‘s hieroglyphs, he arbitrarily divided the characters into letters, one syllable or two syllables.

From here the difference between the two methods and the two results becomes obvious. On one side is Young, the naturalist. Although he was an undeniable genius, he was not educated in literature at school. His approach is schematic. He compared and interpolated wisely. Although he actually deciphered only a few hieroglyphs, the power of his intuition is demonstrated by Champollion’s assertion that Young had correctly described 76 of a list of 221 groups of letters, even though he was ignorant of them. their phonetic value. However, Champollion has mastered more than a dozen ancient languages. Through Coptic he came much closer to the spirit of the ancient Egyptian language than Young. While Young guessed the exact meaning of a handful of single words or letters, Champollion recognized the underlying linguistic system. He goes beyond trivial interpretation; he made Egyptian writing readable and teachable. Once he grasped the basic principles, he saw that decoding must begin with the names of kings. This idea had been lying dormant in his subconscious for a long time.

- The Ark of Achievement is a treasure of the Jewish people, made of gilded wood, containing two stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments”, according to legend, God ordered Moses to make them in the correct size.

But why by the names of kings? The Rosetta Stone inscription, as previously mentioned, is a notice written in three different scripts in which the clergy paid special homage to King Ptolemy Epiphanes. The Greek text can be read in one go, giving us the above content clearly. In hieroglyphic text, there is a group of symbols enclosed in an oval frame, this frame will be understood as cartouche .

Since these cartouches are the only symbols in the text that reveal a particular emphasis, it is reasonable to assume that these cartouches may contain the Egyptian word for the king’s name. Because the king’s name is the only element in the text that has a qualitative difference. And one might think that anyone of average intelligence could pick out the letters of the name Ptolemy (written in the old style) and associate the eight hieroglyphs with the eight letters.

Every great idea is simple in retrospect. Champollion’s achievement was to break away from Horapollon’s tradition, which for fourteen centuries had covered the whole subject of Egyptian writing, and was no ordinary triumph. Moreover, just by luck, Champollion’s theory was brilliantly confirmed when studying the inscriptions on the Philae Pillar, brought back to England by archaeologist Banks in 1821. This column contained a message also written in the same way. pictographic and Greek, similar to the second Rosetta Stone. And here again the name Ptolemy is framed in a cartouche, and there is also another unfamiliar group of hieroglyphs that we know by comparison with the Greek word is the Egyptian word for Cleopatra.

Champollion wrote on paper a group of symbols one above the other in the following form:

From the two “cartouches” on the Philae obelisk, Champollion paved the way for the ultimate decoding of hieroglyphs.

It is obvious that the second, fourth, and fifth symbols in the hieroglyphic group of the word Cleopatra coincide with the fourth, third, and first symbols of the equivalent group of the word Ptolemy. Thanks to that, the key to solving hieroglyphs was found – also the key to opening all the closed doors of ancient Egypt.

The left panel shows how highly developed hieroglyphs (left column) evolved into hieratic (middle column) and then into demonic (right column).

Today we understand how complex the hieroglyphic writing system actually was. Today it is natural for students to learn every detail that Champollion could only master after extraordinary efforts. In his time the language, despite his contribution to thorough understanding, still caused great difficulties, of course, because it contained many variations that had arisen during its three thousand year journey . Today we know much about these variations, dividing “classical” Egyptian from “new” Egyptian, and dividing “new” from “later.” Before Champollion no one noticed this development. A discovery helps a scholar decipher one inscription but fails to decipher the next. The difficulty for the pioneers of hieroglyphics was to grasp a writing style that was evolving in a culture that was completely foreign three thousand years ago.

Nowadays it is quite easy to distinguish phonetic characters from ideographic characters and determiners, a division in the initial valuation of hieroglyphs. Today we no longer get upset when one inscription reads from right to left, another from left to right, and the next from top to bottom. Rosellini in Italy, Leemans in the Netherlands, de Rouge in France, Lepsius and Brugsch in Germany, they all contributed discovery after discovery. Ten thousand papyrus scrolls were brought to Europe, and decoders were eventually able to read a mountain of new inscriptions from tombs, monuments, and temples with ease. Champollion’s Egyptian Grammar ( Paris, 1836-1841) appeared after his death. Then came the first dictionaries of the Ancient Egyptian language, followed by the Records and Monuments . Based on these achievements and later research, Egyptologists over time were able to not only decipher but also write Ancient Egyptian script. The names of Queen Victoria and Duke Albert are inscribed in hieroglyphs in the Egyptian Room of the Crystal Palace in Sydenham. The dedication plaque located in the garden of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin is written in Ancient Egyptian characters. Lepsius attached to the Great Pyramid of Gizeh a tablet on which the name of the tour’s sponsor, King Friederich Wilheim IV, was commemorated in ancient Egyptian script.

The nerdy type of scholar doesn’t always get the luxury of proving his theories directly. Often he did not even have the opportunity to go to places where for decades he had wandered only in his mind.

As it happened with Champollion, he was not lucky enough to add excavation achievements to his purely theoretical conquests. But at least he could visit Egypt and have the satisfaction of testing in the field the theories he had discovered in his private research. From his youth Champollion studied the chronicles and topography of ancient Egypt. Over the years, as he succeeded in determining the space and time of a statue or tablet as accurately as possible with such meager data, one hypothesis followed another. flowing from the waterfall of his imagination. Once he actually set foot in the Egyptian landscape, Champollion was in a situation not unlike that of a zoologist who, having recreated a dinosaur from bones and fossils, suddenly found himself back in the Cretaceous period face to face. with a roaring dinosaur.

Champollion’s tour, which lasted from July 1828 to December 1829, was a triumph. At this time, everyone in Egypt except the French officials had forgotten that Champollion had once been convicted of treason. Local people flocked to see the face of the man who could “read the writing on ancient rocks.” The warm welcome of the Egyptian people inspired the tour group to sing “Marseillaise” [French national anthem] and “Song of Freedom” when solemnly welcoming the Governor of Girgeh province, Mohammed Bey. The group of French people also managed to do some things. Champollion went from discovery to discovery, and found his ideas confirmed with every step. With just a glance, he was able to classify the different eras of structures found in the Memphis ruins. At Mit Rahina he discovered two temples and a cemetery. At Sakkara – which a few years later would see Mariette unearth a number of artefacts – he discovered the name of the Omnos dynasty and thus dated it precisely to the earliest Egyptian times.

The hieroglyphic alphabet (left column) compares with the Latin alphabet (middle column) and the names of the accompanying images

Then he had the sweet satisfaction of proving the assertion that six years before the entire Egyptian committee had laughed at him. The expedition team’s boats anchored at Dendera. On the shore, right in the foreground, are majestic Egyptian temples built by successive generations of kings and conquerors. The kings of the 12th Dynasty during the Middle Kingdom contributed to the construction of the Temple of Dendera, as did Thotmes III and Ramses the Great, the most powerful rulers of the New Kingdom, as well as Ramses’s successor. The Ptolemaic kings also contributed to the construction, and later the Roman emperors, Augustus and Nerva, and finally Domitian and Trajan, the last two figures are remembered for their work in building gates and walls. .