There are few Inca sites that can approach Machu Picchu in majesty, and it is not surprising, because when we talk about Inca constructions the first thing that comes to mind is Machu Picchu. However, Ollantaytambo is one of those constructions as imposing as enigmatic that have managed to overcome the passage of time (even Spanish extirpators of idolatry) to become one of the most important and mysterious sites of Peru with its majestic and colossal architecture. Join the Auri Peru Travel team to explore the details of one of the Inca constructions that can even be compared in majesty to Machu Picchu itself.

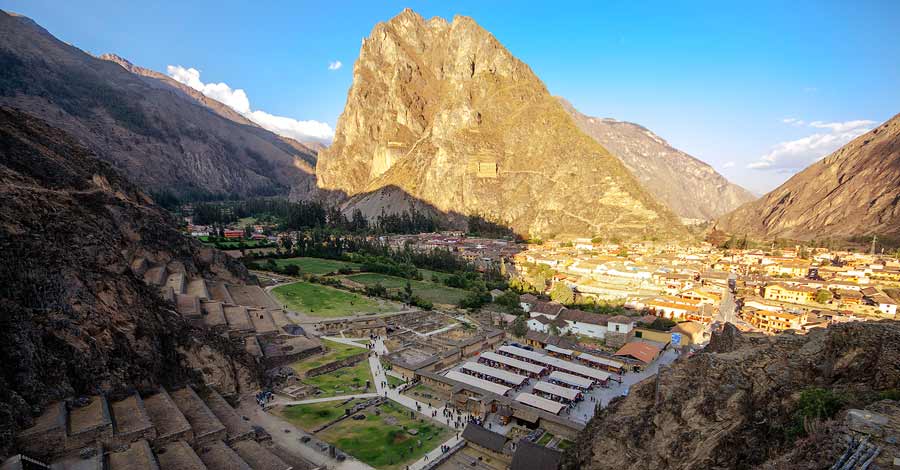

The archaeological park of Ollantaytambo is a “llacta” (Quechua term that is similar to city and used to refer to administrative inca complex) of Inca origin located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas in Cusco. Architecturally speaking, Ollantaytambo presents a complete panorama of the Inca construction phases. This great archaeological complex is located just above the ancient Inca city of Ollantaytambo, today a modern city that preserves many Inca elements and where the train station for Machu Picchu is located, for this last detail, Ollantaytambo is a passing point to reach Machu Picchu.

This great Inca complex is located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas next to the current town of Ollantaytambo, a town known as “The Living Inca Town”. Both (town and archaeological site) are located about 71 kilometers from the city of Cusco and 40 kilometers from Machu Picchu. The Inca complex is crossed by the Patakancha river that flows into the Urubamba river (or Willcamayu river). Ollantaytambo belongs to the province of Urubamba in the Cusco region.

The archaeological park of Ollantaytambo is located at 2922 m.a.s.l. in its highest zone and at 2792 m.a.s.l. in its lowest part, the latter is the same altitude as the actual town of Ollantaytambo.

The weather in the Sacred Valley of the Incas is generally more temperate compared to the city of Cusco. As in the entire Cusco region, the valley has two well-defined seasons: dry season (from April to November) and rainy season (from November to April). The average annual temperature varies between 12 to 24°C during the day, being colder during the nights and conditioned by the dry and rainy seasons.

According to the chronicle sources where Ollantaytambo is mentioned, it can be assumed that the original name of this place was “Tampu”, a word that can be interpreted as a city-lodging for thousands of people. Regarding the current name, there are several theories.

The most popular is the one that says that Ollantaytambo is a hybrid word because of a famous Andean literary work: the drama Ollantay, whose main character is General Ollanta. This Inca drama became popular in the 17th century. According to this literary piece, the scenario where the events of the Inca drama took place is the famous Tambo below the valley of Yucay, that is to say, the current Ollantaytambo. So Ollantaytambo means the Tambo or Tampu of Ollanta according to this version.

Another theory, that of the prestigious linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino, says that the word Ollantay has its origin in the Aymara language, more precisely in the word Ullantawi which means “place of observation from the top”.

Finally, a third version says that the word is mentioned during the distribution of Indians in the sixteenth century, this sector corresponded to Hernando Pizarro. The place was known as Qollaytambo, suggesting that the place means “Qolla”. This is a gentilicio that was used to refer to the inhabitants of the altiplano (Qollasuyo), who, as we will see later, are mentioned in a chronicle as the builders of Ollantaytambo.

Just as it happened with Pisac, it was the Inca Wiracocha who made the first incursions into these territories and his son, the Inca Pachacutec, who would subdue its inhabitants. According to the chronicle of Sarmiento de Gamboa, to the arrival of the Incas, the local ethnic group that inhabited Ollantaytambo was headed by two sinchis (local chiefs) called Paucar Ancho and Tocori Topa. These did not want to give obedience to Pachacutec, they gave them quite a battle even to the point of seriously wounding a brother of Pachacutec.

According to Sarmiento de Gamboa chronicler, the Inca Pachacutec commanded to murder the local people who lived in the zone, burning the town and subjecting them cruelly. Then he ordered to build Tampu, all the current Inca complex according to most chroniclers, except the mestizo chronicler Garcilazo de la Vega, who attributes the construction to the Inca Wiracocha. In any case, the construction would have lasted several decades until it became the architectural wonder it is today.

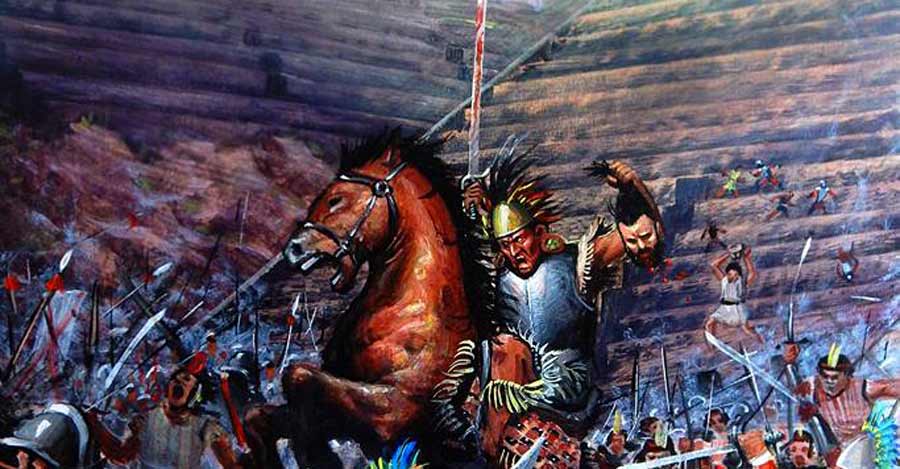

After the arrival of Spaniards and the beginning of Manco Inca’s rebellion, Ollantaytambo would serve as headquarters to direct many attacks on the Spaniards who had captured Cusco, Lima and the central Andes. The chronicler and Spanish soldier Pedro Pizarro mentions that the place was so strong that it was something to be feared.

Manco Inca would resist Hispanic attacks from Ollantaytambo and would lead countless battles throughout the area between Cusco and Ollantaytambo, but after the arrival of Spanish reinforcements from the north and south, he would retreat to the region of Vilcabamba, where he would die as a result of a betrayal years later.

Ollantaytambo would also serve as a base for the Spanish during their intrusions into the mountainous jungle of Vilcabamba to capture the rebellious sons of Manco Inca, the so-called Incas of Vilcabamba.

In 1540 the encomienda of Ollantaytambo was given to Hernando Pizarro, brother of the famous Francisco Pizarro. But later, during the rule of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, the town would be excluded from the encomiendas and would depend directly on the Spanish crown.

The techniques used in the construction of the colossal walls have not yet been fully discovered. Each worked stone is an independent work of art in relation to the others, each one with different angles, sides, and volumes cut with sophisticated techniques that are still the subject of an ongoing debate among researchers.

Ollantaytambo is therefore one of the best Inca mega-works only behind Machu Picchu, although its study represents a real archaeological and architectural puzzle.

This llacta (Inca settlement) fulfilled multifunctional functions. It had a magical-religious, astronomical, administrative, ceremonial, agricultural and even military role. Let’s add that during the rebellion of Manco Inca against the Spaniards, this Inca was in charge of conditioning sectors and reinforcing the complex, fortifying it and making it almost impregnable.

It is a structure whose main facade has six monoliths of Riolita Rosada, a type of headdress brought from the quarry of Cachicata 5 kilometers from the site. The place was destroyed by the extirpators of idolatries because it is believed that it was used to officiate different ceremonies and religious rituals.

It is an Inca wall consisting of ten stone canvases, is the same architectural style that was used in the Qoricancha of Cusco. The enclosure is incomplete because the outer wall and the wall that contained the entrance door was demolished. This enclosure is a great portent of architecture and engineering, I can be associated with the so-called temple of the sun.

There are five beautifully carved protuberances in Ollantaytambo. It is believed that they fulfilled astronomical functions. Many people assume that the carvings in this area were made by non-human technology, but without any valid argumentation other than mere speculation. There are also those who associate it with the shape of a condor and made by pre-Inca civilizations. The truth is that there is still much to investigate.

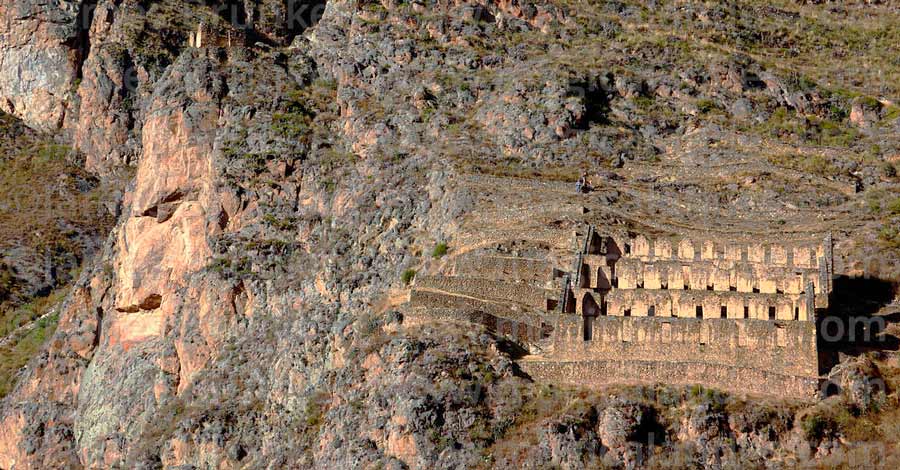

These constructions fulfilled a very important role, since foodstuffs were stored here. The characteristics of these constructions ensured that the food was preserved in spite of the weather conditions. In Ollantaytambo there are about 30 colcas with no apparent order.

There are a series of fountains and waterfalls in Ollantaytambo, today they are popularly known as “Temple of Water” and the “Bath of the Ñusta”. All these fountains must have served liturgical and ceremonial purposes to sacralize the water and as commonly believed for toilet functions.

This is the name given to the current street where both pedestrians and vehicles enter Ollantaytambo. Here there are remains of a very long wall with many niches (it is estimated that there may have been between 80 to 100). Towards the right side the street shows remains of strong walls finely coupled like those of Hatuntumiyoc street (where the 12 angles stone is found). The wall containing the niches was probably the inner face of a wall of a long succession of enclosures that no longer exist today.

From Pachar, about two 10 minutes before entering Ollantaytambo, a series of parallel terraces can be seen on both sides of the Urubamba River. Inside the Inca site we find terraces that have completely transformed the landscape with its up to 700 meters deep. Nearby we also find terraces that served agricultural and even defensive functions. Within the inca city, they were used to cement complex buildings in unstable terrain or located on the edge of the mountains and of course without neglecting their agricultural function.

Ollantaytambo presents pukaras or military constructions. One of these is called Choqana and is located two kilometers from Ollantaytambo. Besides the military functions that are believed to have been fulfilled, it is also presumed that it had administrative and communication functions. It has a good water supply, food deposits and many constructions that according to the Cusquenian historian Victor Angles Vargas were the refuge of the sentinels.

In front of Choqana another fort was built, complemented by a superb wall associated with upper towers, roads, aqueducts and enclosures. The whole sector is called Inkapintay.

It is located almost in front of the train station, on the left bank of the Urubamba River. It has similar characteristics to Choqana. It is made up of enclosures, aqueducts, trails and some platforms.

For many guides and local people related to mystical or esoteric tourism, in Ollantaytambo was represented in stone an envoy of Wiracocha (supreme god of Andean mythology), a preacher character endowed with supernatural powers called Tunupa or Wiracochan.

According to these theories, Wiracochan or Tunupa is the representation of the cosmic vitality of the Andean god Wiracocha through his envoy. The representation of the face of this envoy is found in the Pinkuylluna mountain, from where it is said that he establishes a connection with the Pleiades (protective constellation of the Andean corn) to determine the variations of the stars with the passing of the years and to make possible the reform of the Andean calendars.

However, other theories suggest that this character, who is mentioned in the chronicles of Santa Cruz Pachacuti and Guaman Poma de Ayala (chroniclers strongly influenced by Christianity), is related to the apostle Santo Tomas. At a certain moment in Peruvian history, Christianity replaced the character of Tunupa with the Christian apostle Santo Tomas in the Andean myths, even replacing indistinctly the god Wiracocha by the apostle.

Chroniclers such as Cieza de León and Sarmiento de Gamboa also mention the character, but he is often confused with Wiracocha, although his origin is always associated with the Peruvian-Bolivian altiplano. In other words, the myths about this god or his envoys are found in the altiplano and all the areas around Lake Titicaca, even reaching well south of Cusco (Raqchi).

In Ollantaytambo, there is no indication that the local inhabitants have venerated the deity known as Tunupa (although the Incas did know Wiracocha), unless this has been kept in the collective memory until the arrival of these theories related to mystical tourism. In addition, if the rock had been carved by the Incas, the finish would have been much more perfect due to the Incas’ mastery in stone carving.

It is curious how in Ollantaytambo some areas of cultivation, its limits and its slopes in the valley have the apparent form of a pyramid seen from the distance. The area covered is 14 hectares, and is much talked about by guides and people associated with mystical or esoteric tourism. However, the Inca civilization was not characterized precisely by building pyramids like those of Egypt, Central America or the coast of Peru. According to some mystical theories, phenomena related to solar hierophany, in other words, man-made light effects for sacred purposes, are produced here.

Mystical tourism guides mention that this pyramid is related to Pacareqtambo, the place of origin of the Incas according to Andean mythology and that the “windows” of this pacarina (places of origin in the Andean world) connect with the spiritual Andean worlds: Hanan Pacha, Kay Pacha and Uku Pacha. Finally, for other people, this “pyramid” represents a stylized Inca ushnu or altar.

There is a very striking detail in the Maskabamba sector very close to Ollantaytambo. On the beautiful Inca terraces that once contributed to the defense of Manco Inca’s army in Ollantaytambo, we find a half-body bust painted in red and white that represents Manco Inca after repelling the violent attack of the European invaders commanded by Hernando Pizarro during the defense of Ollantaytambo.

According to Guamán Poma de Ayala, Manco Inca had it painted after his victorious battle against the Hispanics. Sometime later he would choose to retire to Vilcabamba. The area where this painting is located is called Inkapintay.

If we wonder about the quarry from which the rocky material for the construction of the place would have been provided, we have to refer to the quarry of Cachicata.

This quarry is located in a transversal ravine that culminates in the Urubamba River. The place is 5 kilometers away in a straight line from Ollantaytambo and if we measure the road infrastructure that was used by the Incas, it adds up to a total of 8.8 kilometers. That’s right, the Incas moved the rocks for more than eight kilometers down the mountain and back up to the other mountain where Ollantaytambo was built, a more than amazing effort.

Cachicata translates as “salt slope”. Throughout this area there are traces of the enormous work that had to be done to extract and move the rocks, as we find blocks of stone abandoned halfway, the locals call them “tired stones”. On the other hand, there are multiple options of treks and day tours to visit these Inca quarries and the Inca unit called Intipunku.

The current town is popularly known as “The Living Inca Town” because it preserves the layout of the original Inca city. As in other towns in the Sacred Valley, a good percentage of the inhabitants speak Quechua. The population is divided by the Patakancha river, the eastern sector where the town square is located is called Qosqo Ayllu, while the western sector is called Araqama Ayllu, in the latter sector is located the impotent archaeological complex.

We could summarize that the town is a sort of museum with its cobblestone streets, houses that preserve Inca walls, its aqueducts and other Inca elements that still persist in the place.

Currently, there are multiple options to get to Machu Picchu, one of these being to opt for train services to the town of Aguas Calientes (the closest town to Machu Picchu). There are two train stations on this route to reach Machu Picchu, the first station is located in Poroy (30 minutes from the city of Cusco) and the second is located precisely in the town of Ollantaytambo (an hour and a half from Cusco).

The Ollantaytambo train station is located 10 minutes southeast of the town square. It has two operators of passenger transportation services: Peru Rail and Inca Rail. Both offer short section service from this station. The total trip takes one hour and 45 minutes, about 2 hours less to reach Aguas Calientes compared to leaving from Poroy station.

The Ollantaytambo train station has ticket offices, a cafeteria, waiting rooms and public restrooms. Around the train station, you can find restaurants, transportation service to Cusco and commercial stands with essential products for a traveler.