Gamers the world over will be familiar with the incredibly detailed historic cityscapes the Assassin’s Creed franchise has produced so far. Following earlier forays into ancient Damascus and Athens, the forthcoming instalment, Mirage, takes players into ninth-century Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid caliphate.

As an expert in Islamic architecture, art, and history, I worked with world design director Maxime Durand and Mirage historian Raphaël Weyland to bolster the game’s historical grounding, including the new educational feature, entitled The History of Baghdad. Gamers will be able to explore, in an interactive way, the economy, government, arts, beliefs and daily life of the time.

Little of medieval Baghdad remains today. In the 13th century, the city was sacked by the Mongols and mostly destroyed. To my mind, though, this very absence of archaeological evidence from the ninth century has been an opportunity to showcase the diversity of Islamic art and architecture.

Baghdad, the Round City

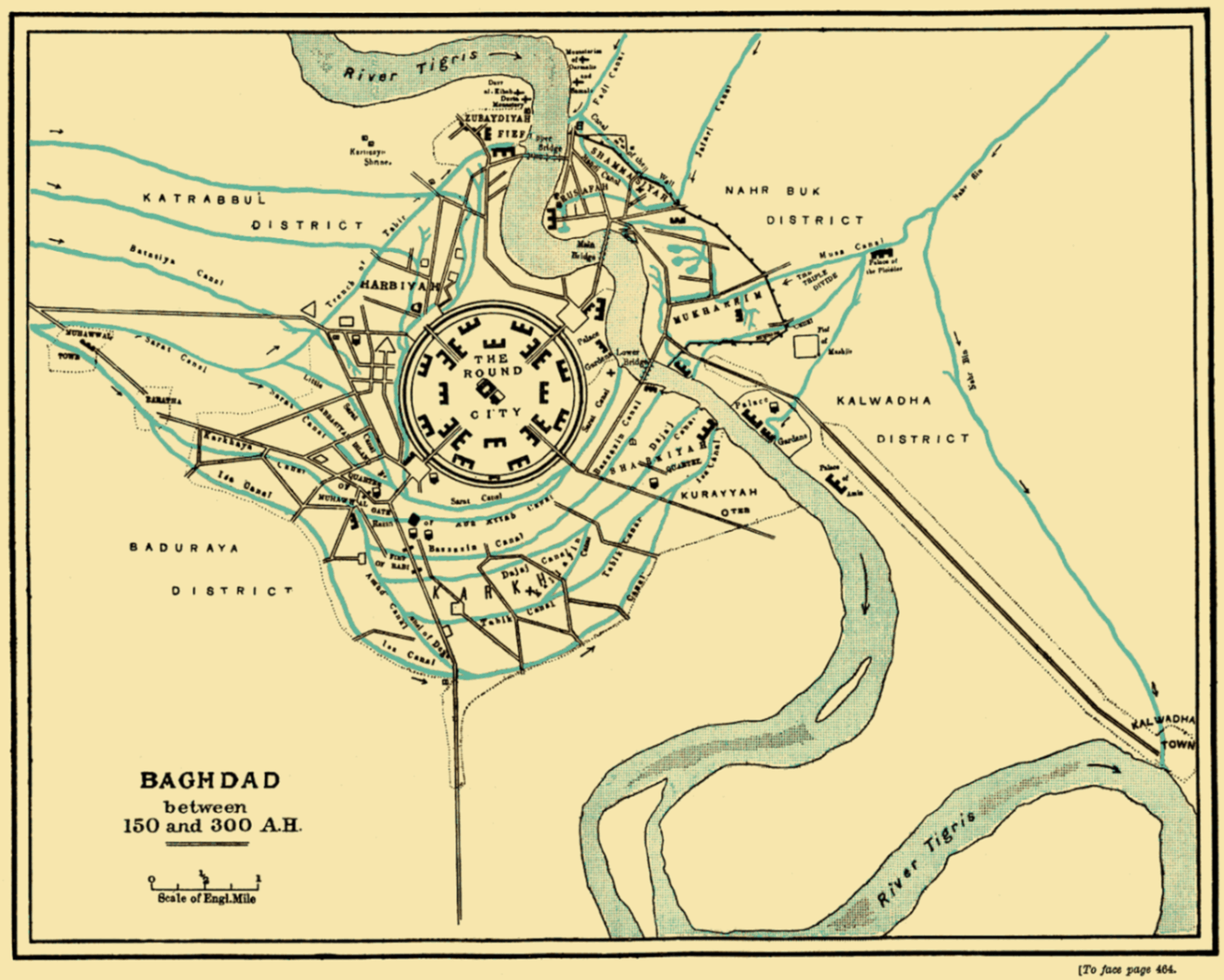

Generations of medieval scholars described, in minute detail, what Baghdad had been before the Mongol invasion in 1258. Founded in 762 by al-Mansur, the Abbasid caliph or ruler, Baghdad was one of the largest and most important cities of the medieval globe. It was a focal point of international politics, intellectual life, the arts and a booming global economy.

Architectural historians Saba Sami Al-Ali and Nawar Sami Al-Ali have discussed how, despite the lack of archaeological remains, scholars have long reconstructed the Round City’s basic parts.

Built on a circular plan, Baghdad continued ancient Sasanian urban planning practices. In the 9th century, it measured about 3,000 metres in diameter and was built of mud-brick, the favoured building material of this region since antiquity.

The city counted two concentric circular walls, surrounded by a moat and punctuated by four domed gates, each topped with a figure holding a lance. Within the walls was a vast empty space. The massive domed Golden Palace of the Abbasid caliph rose at its centre.

Next to the palace was the main mosque, described as being half the size of the palace, as well as elite houses and official government spaces. Grand avenues led from the domed gates to the surrounding quarters and suburbs, where there were other palaces, gardens, canals, bridges, houses, markets, baths and industrial areas.

The archeological remains in Baghdad today date, in fact, back to the 13th century, the later Abbasid period. The Mustansiryya Madrasa, which was one of the city’s most important educational institutions, boasts a 16-metre tall monumental gate with intricate geometric patterning and a long inscription dedicated to the building’s patron, Al-Mustansir.

Elsewhere, there are fragments of a minaret that was once part of the al-Khulafa Mosque and the Dhafariya (or al-Wastani) Gate. There is also the shrine of ‘Umar al-Surawardi, a 12th-century Persian sufi. This mausoleum and mosque complex features a conical muqarnas dome, the design of which is typical of the region from the 11th century.

A lack of archeological evidence

The Islamic art historian Bernard O’Kane has proposed that a marble prayer niche (or mihrab), preserved today in the Iraqi National Museum, may be one surviving remnant from the ninth-century palace city. Nothing else remains, though, from before the Mongol sacking.

The best evidence for what the city looked like at the time is found in other archaeological sites. Research has shown that two cities – Al-Rafiqa, at Raqqa in Syria and Qadisiyya (or al-Mubarak), near Baghdad – were effectively imitations of the Round City.

The archeological site of Samarra provides even more clues. Founded in the 9th century, this ancient Islamic city housed the Abbasid court and its military. Its huge brick palaces and monumental gates suggest what visitors to Abbasid Baghdad would have encountered. Mosques, minarets and houses would likely have been decorated with similar carved and painted stucco, ceramic and glass tiles and shimmering mosaics.

Baghdad, as presented in the Mirage trailers, is breathtaking. It’s also completely fantastical – a Baghdad that never was.

In the art and architecture it comprises, the game evokes a plethora of other times and places beyond Baghdad and the caliphal age – from Isfahan and Delhi to Samarkand. Encased within the Round City gamers may encounter elements reminiscent of medieval North African gates and fountains, early modern Iranian bazaars and mosques, the domed tombs from south and central Asia and the tiled interiors from the Iberian peninsula.

Scholars of Islamic art and architecture may be disappointed – dismayed, even – at these liberties taken. To my mind, though, this has represented an opportunity to showcase the riches of Islamic art and architecture, across space and time.

Islamic architecture is one of the world’s great traditions, yet also one of the most misunderstood and unfamiliar to those outside of the Muslim-majority regions of the world. Most people are simply not familiar with it – certainly not the way they are with Egyptian, Greek, or Roman architecture, or the various European traditions.

What people think they know about the visual culture of Muslim societies is also not supported by historical evidence. To give just one example, the oft-repeated and false notion that figural representation is forbidden in Islamic art.

Mirage is an homage to the history of Islamic art and architecture, across centuries and regions. Making these riches visible and relevant to today’s global audiences may well be the game’s most significant contribution.