A copper dome, originally believed to be an oversized cooking cauldron, has ignited excitement in the maritime archaeology community as it may well be the remains of a 17th-century primitive submarine, possibly one of the earliest ever discovered.

This intriguing find was made in 1980 near the sunken wreckage of the Santa Margarita, a Spanish treasure galleon that met its demise in 1622 within the Florida Straits, just 40 miles west of Key West. Over the years, the object, measuring 147 centimeters (58 inches) in diameter, has been on display at the Mel Fisher Museum in Sebastian, Florida.

Now, in a revelation that could rewrite history, maritime archaeologists Sean Kingsley and Jim Sinclair have put forward a compelling case in the latest edition of Wreckwatch Magazine, proposing that this enigmatic artifact is, in fact, the upper section of an early diving bell utilized by treasure hunters to salvage riches from the shipwreck.

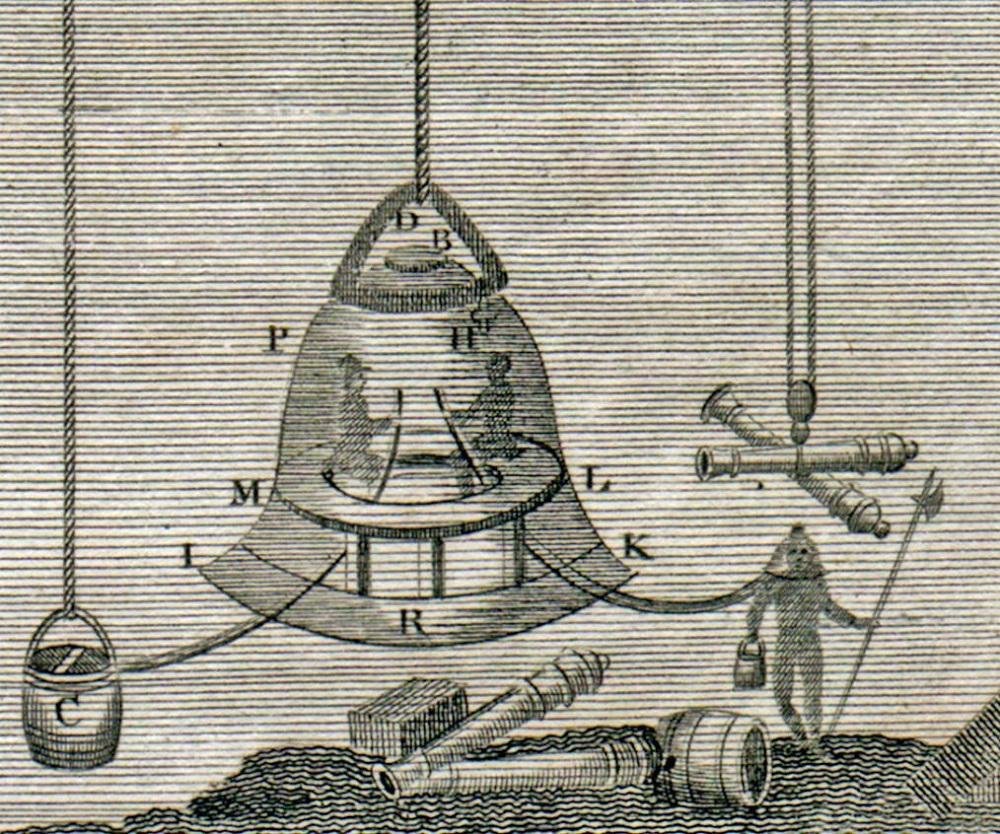

These primitive diving bells were predominantly employed in shallow waters and were characterized by their open bottoms, filled with air to provide divers with a pocket of breathable atmosphere at varying depths.

The dimensions and construction of this copper dome defy the notion that it was a mere cauldron for cooking. Crafted from two copper sheets, it features a robust rim studded with copper rivets, displaying no signs of charring or heating.

This intriguing object aligns more closely with historical descriptions of diving bells from the 17th century. While it is yet to undergo peer-reviewed scrutiny, the evidence presented by Kingsley and Sinclair appears highly compelling.

Furthermore, the dome was found in proximity to iron ingots that might have served as anchors, securing the device to the seabed. Though historical records do not explicitly mention a diving bell being employed in the salvage operation of the Santa Margarita, it’s worth noting that Spanish pioneers in maritime innovation, notably Jerónimo de Ayanz, had designed diving bells as early as 1606. Ayanz’s invention had later been utilized for pearl diving in Venezuela.

The researchers propose that this particular diving bell, possibly comprising the upper section of the apparatus, would have been accompanied by a series of watertight lower panels, likely constructed from wood and leather, which have since been lost to time. The diving bell itself could have accommodated up to three divers and may have been tethered to a surface support vessel via an air hose.

What lends further credence to this theory is the astonishing success reported in the 17th-century Santa Margarita salvage operation. Francisco Nuñez Melián, a Spanish salvager based in Havana at the time, recounted their recovery of 350 silver ingots, thousands of gold coins, and even eight cannons from the wreckage. Such an impressive haul strongly suggests the employment of a diving bell, a tool designed to facilitate underwater retrieval of valuable cargo.

While the precise nature of this artifact is yet to be conclusively determined, Joseph Eliav, a maritime archaeologist at the University of Haifa, told Live Science that it was possible the mysterious object was part of an early diving bell. Based on photographic evidence, Eliav noted that the seam between the lower sections and the dome, which is held together by a ring of rivets, could provide valuable insights.

“All I can say, based on the photographs, is that this artifact being the top of a diving bell is a plausible hypothesis,” he said in an email. If any indications of a seal, caulking, or perhaps even welding are discovered in this seam, it would significantly support the hypothesis.

Further research is necessary to definitively confirm the identity of this remarkable artifact, but it undoubtedly sheds light on the remarkable ingenuity and resourcefulness of 17th-century maritime pioneers.