Every year, thanks to poachers, 30,000 species have been pushed into extinction. And in Africa alone, 96 elephants a day are killed by these poachers. But in Zimbabwe, efforts are being made to turn the tide against this illegal activity.

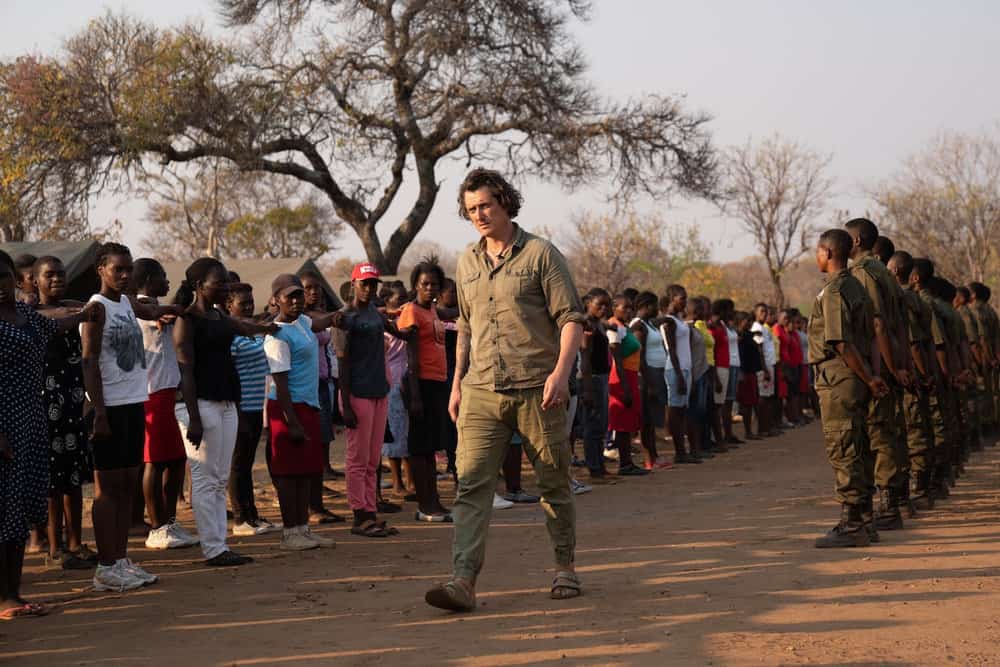

Through his International Anti-Poaching Organization, Australian veteran Damien Mander brought together a group of skilled women to lead the command. These women are the Akashinga rangers, an all-female anti-poaching unit that is changing conservation work in Africa.

Akashinga, which means “brave people,” is an elite team that engages with the community to help change local people’s perceptions of wildlife. And in doing so, they are saving species and promoting biodiversity.

A new National Geographic documentary by executive producer James Cameron and director Maria Wilhelm returned backstage and captured the stories of Mander and these incredible women.

Coaching rookies in team building, leadership, unarmed combat, patrol, wildlife awareness, and conservation ethics, Mander uses her special forces platform to empower the team. These women are now engaged, both socially and economically, with their community like never before, and the results are staggering. Now, Mander hopes to grow the team to 1,000 rangers and keep the ball going.

We had the opportunity to speak with Mander, as well as Akashinga’s ranger Nyaradzo Hoto about the group’s important role in conservation and how this work has changed the community for the better. Read on to the My Modern Met interview and watch the full documentary.

What motivated you to participate in the anti-poaching movement?

Damien Mander: I came from an Australian Navy clearance diver and then took part in special operations. I continued to work in Iraq for three years as part of the alliance’s effort. My career, until moving to Africa, was working in men’s-only units.

I founded the International Anti-Poaching Foundation in 2009. I wanted to bring a similar theme from my military days into conservation. Initially, it worked, and we achieved great results. But constant conflict with local communities makes me rethink all the mistakes we made in Iraq. We have to think hard. While I see other industries progressing with more women in management, conservation is still becoming stifling.

An article in The New York Times, in early 2017, about how the US Army Rangers put women in training for deployment made me hard to see. Ten years ago, our convoy was hit by a bullet while on duty in Baghdad, and the United States Army Ranger rescued us. If the unit is good enough and good enough to save my life and is deploying women as Rangers, maybe women can also be wildlife rangers. And the right people, not just stuck at checkpoints or ride tables – all responsibility and opportunity rest on their shoulders.

How did Akashinga’s first team come about, and why did you choose them specifically?

DM: From 2009 to 2017, the IAPF ran conservation programs primarily focused on law enforcement. In conservation, tactics are increasingly militarized worldwide in retaliation for poaching and desperation to protect what remains.

We want to explore new ways of conservation and community reunification. So in August 2017, we began recruiting and training the world’s first all-female armed anti-poaching unit at an abandoned trophy-hunting sanctuary in Zimbabwe.

They made more than 200 arrests in the first three years of operations. The women helped avert 80% of the decline in elephant poaching in Lower Zambezi Valley and Central Zimbabwe, one of the world’s largest leftovers. This concept has now been implemented, and we are in the process of training an additional 240 women for full-time positions as we scale up to 1000 rangers and list 20 parks by 2025.

It is a strong message to see women take on this issue. How do you see their work changing the local attitudes about the role of women?

DM: Akashinga rangers are taking on one of the most serious and respected jobs in the world while at the same time growing that work and building their lives, families, and communities in the process submit. And it’s all based on plant-based diets.

In Africa, men have traditionally taken most of the frontline positions in conservation. Still, locals now realize the tremendous benefits of putting women at the center of conservation efforts community-led. We have changed our strategy for wildlife conservation. We place women’s empowerment at the heart of the strategy. That gave us the greatest momentum in community development, and conservation has become a biological product.

What future plans do you have to help end poaching, particularly elephant poaching in Zimbabwe?

DM: Zimbabwe is home to the world’s second-largest elephant population, and as poaching intensifies, Akashinga rangers are essential to the protection of this vulnerable species. As we expand, we will contract more and more wildlife that would otherwise be lost in partnership with local authorities and communities. In the process, we will preserve biodiversity. This is key, not just elephants.]

What do you hope people lose by watching a documentary?

DM: We are very grateful for the documentary that has helped bring women and the show a global voice. We believe that this voice will be a key ingredient in helping us grow our program towards those 1,000 rangers.

How was your first time as a ranger, and what attracted you to your job?

Nyaradzo Hoto: I first heard the news of the newly formed all-female Akashinga unit from one of our community area council members. My passion for wildlife and nature attracted me to this job.

How did being an Akashinga ranger change your life?

NH: Through Akashinga, I got my driver’s license, a big deal for a rural African woman. I have been promoted to sergeant, and I just came out of dust when I joined Akashinga. I have been trying to follow my educational dreams since dropping out of school years before.

I am currently a part-time student at one of the Universities in Zimbabwe, earning an honorary degree in wildlife, ecology, and conservation. I also bought a piece of land in our community not far from the school that I had been forced to drop out of years earlier.

What is the most rewarding reward for your job?

ADVERTISEMENT

NH: It is very rewarding to make a difference in protecting wildlife and nature while educating others to respect and share conservation values. I work with like-minded, active, conservation-oriented women who are capable of achieving great things. I find that to be useful.

Do you want people outside of Africa to know what you do and why it is important?

NH: Akashinga is a community-driven conservation model with a mission to empower women to restore and manage a network of wildlife as an alternative economic model for hunting catches the cup.

Our bold goal is to recruit 1,000 female rangers to protect a network of 20 nature reserves under IAPF management by 2025. Our focus in Africa is on recruiting and growing locally. We are not only about protecting the natural world but also about bringing communities and conservation together.

Watch the full documentary below: