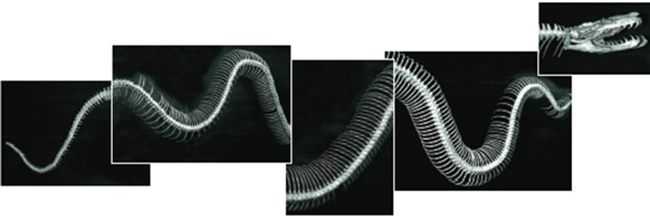

Ralph was even longer than this reticulated python (Photo: Tropenmuseum, National Museum of World Cultures/Wikimedia)

In a backroom at Cornell’s Museum of Vertebrates, the skeleton of Ralph, the McJunkin family python, is hanging on a wall. In life, Ralph was a lady snake and measured 26 feet long. In death, she spent decades stored in the McJunkin home, where she was brought out on holidays for the younger McJunkins to reassemble, before she was donated to Cornell and became one of the longest snake skeletons in any museum in the world.

Ralph once lived in the Philippines, on the northern end of Luzon, the largest island in the archipelago. In 1915, Norman L. McJunkin, an American, was working for the Army’s bureau of insular affairs and setting up schools in the same area. One night, on a hunting trip in the mountains, he and a group of both army officers and locals were sitting around their campfire, when they heard a rustling in the trees above. McJunkin shot into the trees, and the creature that was up there fell to the ground.

In the light of the next morning, the hunting party found Ralph dead on the ground. They draped her body around nearby anthills, giant ones that reached 10 feet tall, and left her to the insects and scavengers. Within days, her bones were fleshless.

Ralph, in all her glory (Photo: Courtesy of Cornell Alumni Magazine)

Around this time, when it was trendy for white men to adventure through jungles, tales of giant snakes abounded, but facts about these snakes were slippery. Roy Chapman Andrews, a world-traveling taxidermist who’s often said to be a model for Indiana Jones, shot a python 20 feet long and as thick as his own waist. That story’s true. Percy Fawcett, the British explorer who disappeared in the Amazon while searching for the lost city of Z, said he had killed an anaconda 62 feet long. No one believed him. Another explorer said he’d found an anaconda that was 100 feet long and weighed five tons. That seemed even less likely.

There are only a few species of snake in the world that reach longer than 20 feet, and as Harry Greene, a Cornell herpetologist, writes in his book Tracks and Shadows, no one has ever captured a live snake longer than 30 feet. When snakes do reach those incredible lengths, they’re female snakes. Ralph is a reticulated python, and as Greene explains, males of that species occasionally reach 15 feet.

The longer a female python is, the more eggs she can produce. A reticulated python’s eggs, approximately four inches long and two wide, can weigh half a pound, and while an average clutch might contain 24 eggs, a long snake can have 70.

A reticulated python (Photo: The Cambridge natural history/flickr)

In 1915, though, no one realized that Ralph was a female snake. McJunkin brought the skeleton home and stored it in two cardboard boxes. The spine was strung together, and on family holidays, Norman’s son, Reed, would lay it across the living room floor, he told Cornell Alumni Magazine.

Reed inherited Ralph, and in 2003, he decided to donate the snake to his alma mater. Greene and two snake anatomists again laid the snake out on a living room floor. Examining Ralph, the scientists found that even before her death, she had lived hard. Fifty of her ribs had been fractured at some point, and her backbone had been damaged, too.

Ralph had 357 vertebrae, and the scientists checked that each was in its proper position, before arranging the ribs (100 of which were missing) according to size along the snake’s spine. Without the snake’s soft tissue, the skeleton would be shorter than the snake had been in life, but when they were finished, the scientists had 20 feet of snake skeleton, longer than any snake skeleton in any museum Greene could find at the time.

In 2009, paleontologists discovered the bones of Titanoboa, a 40-foot long prehistoric snake, the largest ever known. Ralph may not be able to compete with a giant prehistoric relative, but even now she is still one of the largest snakes in any collection, anywhere in the world. The skeleton now stays in a display case in front of the Museum of Vertebrates teaching lab; visitors can request to see it, or go on a tour of the building–Ralph is one of the highlights.