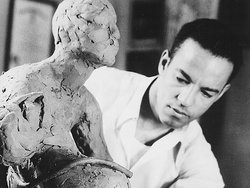

JAMES RICHMOND BARTHE (known

as Richmond Barthé) was an African-American sculptor associated

with the Harlem Renaissance. He is best known for his portrayal of black

subjects. The focus of his artistic work was portraying the diversity and spirituality

of man. He once said: “All my life I have been interested in trying to

capture the spiritual quality I see and feel in people, and I feel that the

human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in

man.”

He became

one of 20th century America’s

greatest sculptors of the human form, and Mississippi’s preeminent artist in the

field.

Richmond was born in Bay St.

Louis, Mississippi. His father died at age 22, when Richmond was only a

few months old, leaving his mother to raise him alone, working as a dressmaker.

Richmond showed a passion and skill for

drawing from an early age. His mother was, in many ways, instrumental in his

decision to pursue art as a vocation. He once said: “When I was crawling

on the floor, my mother gave me paper and pencil to play with. It kept me quiet

while she did her errands. At six years old I started painting. A lady my

mother sewed for gave me a set of watercolors. By that time, I could draw very

well.”

His

teachers in grammar school encouraged him and when he was only twelve years

old, he exhibited his work at the Bay St. Louis Country Fair.

Richmond was beset with health

problems, and after an attack of typhoid fever at age 14, he withdrew

from school. Following this, he worked as a houseboy and handyman,

but still spent his free time drawing. A wealthy family, the Ponds, who spent

summers at Bay St. Louis, invited him to work for them as a houseboy in New Orleans.

Through his

employment with the Ponds, Richmond broadened

his cultural horizons and knowledge of art, and was introduced to Lyle

Saxon, a local writer for the Times Picayune. Saxon was fighting against

the racist system of school segregation, and tried unsuccessfully to get Richmond registered in an art school in New Orleans.

In 1924,Richmond donated

In 1924,Richmond donated

his first oil painting to a local Catholic church to be auctioned at a

fundraiser. Impressed by his talent, Reverend Harry F. Kane

encouraged him to pursue his artistic career and raised money for

him to undertake studies in fine art.

At age 23,

with less than a high school education and no formal training in art, Richmond applied to

the Art Institute of Chicago, and was accepted. He became one

of 20th century America’s

greatest sculptors of the human form, and Mississippi’s preeminent artist in the field.

While many young artists found it very

While many young artists found it very

difficult to earn a living from their art during the Great

Depression, the 1930s were Richmond

‘s most prolific years. The

shift from the Art Institute of Chicago to New York City, where he moved following

graduation, exposed him to new experiences. He established his studio in Harlem in 1930

after winning the Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship at his

first solo exhibition in Chicago.

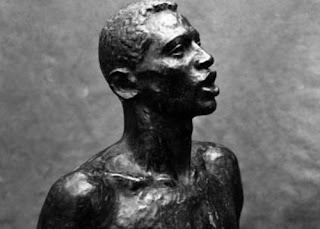

Richmond mingled with the bohemian circles of downtown Manhattan. Initially

unable to afford live models, he sought and found inspiration from on-stage

performers. Living downtown provided him the opportunity to socialize not only

among collectors but also among artists, dance performers, and actors. His

remarkable visual memory permitted him to work without models, producing

numerous representations of the human body in movement.

His works

were exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. In summer

1934, Richmond went on a tour to Paris with Reverend Edward F. Murphy, a friend of Reverend

Kane from New Orleans,

who exchanged his first class ticket for two third-class tickets to share with Richmond.

This trip exposed him to classical art,

but also to performers such as Josephine

Baker, of whom he made portraits in 1935 and 1951.

During the

next two decades, he built his reputation as a sculptor. He was awarded several

awards and experienced success after success and was considered by writers and

critics as one of the leading “moderns” of his time.

In 1945, Richmond became a member

of the National Sculpture Society. The tense environment and violence of the city

began to take its toll, and he decided to abandon his life of fame and move to Jamaica in the West Indies

in 1947.

His career flourished in Jamaica, and he remained there

until the mid-1960s when ever-growing violence forced him to move again.

For

For

the next five years, he lived in Switzerland,

Spain, and Italy, then settled in Pasadena, California

in a rental apartment. In this apartment, Richmond worked on his memoirs, and

most importantly, editioned many of his works with the financial assistance of

actor James Garner until his death in 1989.

Garner copyrighted Richmond’s

artwork, hired a biographer to organize and document his work, and established

the Richmond Barthe Trust.

Richmond was a devoted Catholic. Many of his

later works depicted religious subjects,

including John the Baptist (1942), Come Unto Me (1945), Head

of Jesus (1949), Angry Christ (1946), and Resurrection (1969).

Works like The Mother (1935) (see right), Mary (1945), or his

unfinished Crucifixion (ca. 1944) are noticeably influenced by the

interracial justice for what he was awarded the James J. Hoey Award by the

Catholic Interracial Council in 1945.