Of all the world’s lost cities, none surely can compete for evocative splendour, age or mystery with Babylon. Here on the desert plains 60 miles south of Baghdad, where the sun turns horizons into flashing pools of mercury, is where so much human history began.

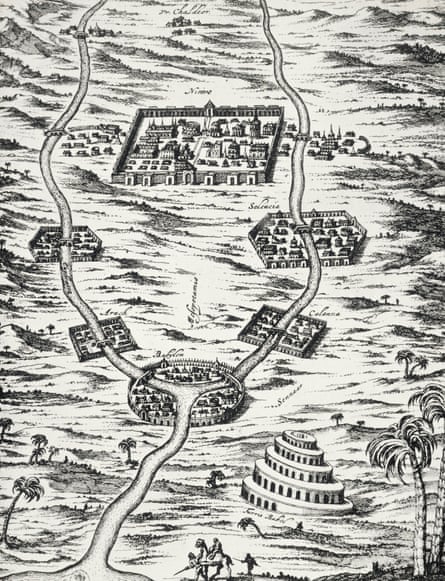

Land of the Fertile Crescent, bounded by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, this is successively the realm of Sumer and Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Mesopotamia and Iraq. Adam and Eve’s Garden of Eden is said to have been nearby.

If Mesopotamia is the cradle of urban civilisation, Babylon is its firstborn child. First mentioned in the 23rd century BC, it looms larger in the records from around 1792 BC, the beginning of the reign of Hammurabi.

Babylon’s second most famous king is remembered for his uncompromising code of laws – many ending with the ominous phrase: “He shall be put to death” – which sit today in the Louvre on an eight-foot stela of carved black diorite. Hammurabi was the first to fashion Babylon into the capital of a kingdom encompassing southern Mesopotamia and part of Assyria in northern Iraq.

But the Babylon that elicits a thrill in anyone with a passing interest in history is the city of that Old Testament anti-hero: the Jew-slaying, temple-smashing, gold-loving despot Nebuchadnezzar II, who succeeded to the throne in 605 BC.

Flush from a whirlwind of military conquest in Egypt and Syria, Nebuchadnezzar plunged into a monumental building programme which resulted in the largest, most glorious city of the ancient world. It was a dazzling urban vista of towering temples, shrines and palaces clad in blue-glazed tiles, resplendent in gold, silver and bronze; all encircled by city walls so massive that two chariots, each drawn by four horses, could pass each other with ease on the road that ran atop them, according to the Greek geographer Strabo.

Nebuchadnezzar’s imperial frenzy of construction also produced the city’s most celebrated monument, a construction so hubristic in ambition it became the most famous building in the world, a byword for mankind’s god-rivalling arrogance. Babylonians knew it as the 91-metre tower – or ziggurat – of Etemenanki on the top of the temple of Marduk, the “house of the frontier between heaven and earth”. The rest of the world, starting with Old Testament readers, knew it as the Tower of Babel. In the words of its royal inscription:

As to Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon, of which Nabopolossar, king of Babylon, my father, my begetter, had fixed the foundation – and had raised it 30 cubits but had not erected its top, I set my hand to build it. Great cedars which were on Mount Lebanon in its forest, with my clean hands, I cut down, and placed them for its roof.”

What we know about Babylon comes from a combination of classical scholars – Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian of the fifth century BC, foremost among them – archaeological excavations and the evidence of cuneiform texts. Herodotus provides one of the earliest and most detailed descriptions of Babylon. In his one-volume masterpiece the Histories, he devotes 10 pages to the city, a typically Herodotean blend of fact, probable fantasy and a dollop of sex to keep his audience interested.

“Babylon lies in a wide plain, a vast city in the form of a square with sides nearly 14 miles long and a circuit of some 56 miles, and in addition to its enormous size it surpasses in splendour any city of the known world,” he begins. “It is surrounded by a broad deep moat full of water, and within the moat there is a wall 50 royal cubits wide and 200 high.”

Herodotus also provides a graphic description of the temple of Marduk, the dominant feature of the city on what was then the east bank of the Euphrates.

“The temple is a square building, two furlongs in each way, with bronze gates, and was still in existence in my time; it has a solid central tower, one furlong square, with a second erected on top of it and then a third, and so on up to eight. All eight towers can be climbed by a spiral way running round the outside, and about half-way up there are seats and a shelter for those who make the ascent to rest on. On the summit of the topmost tower stands a great temple …”

There were a number of smaller temples in this eastern, older section of the city, together with quays for merchant ships, an indicator of Babylon’s rise to fabulous prosperity through conquest and trade. Within a neat grid of streets the central and most important artery was the Processional Way, a paved road running north through the Ishtar Gate, embellished with bulls and dragons in relief, to the Bit Akitu temple, the “House of the New Year’s Festival”. Two great palace complexes rambled across 40 acres of land to the west of the Ishtar Gate, one of Babylon’s eight fortified defences.

Nebuchadnezzar’s boastful inscriptions on baked bricks, which followed the tradition of Babylonian kings relating their architectural rather than military achievements, offer valuable clues about the city. In one, he talks about work on two gates along the Processional Way.

I laid their foundations of mortar and bricks and with shining blue glaze tiles with pictures of bulls and awful dragons I adorned the interior; mighty cedars to roof them over I caused to be stretched out, the wings of the gates of cedar wood coated with bronze, the lintels and the door knobs of brass I fastened into the openings of the gates; massive bulls of bronze and dreadful, awe-inspiring serpents I set up at their thresholds, the two gates I ornamented with great splendour to the amazement of all men. In order that the onslaught of battle might not draw nigh to Imgur-Bel, the wall of Babylon.”

In 597 BC, Nebuchadnezzar attacked and seized Jerusalem. The Book of Kings describes how he “carried away all Jerusalem, and all the princes, and all the mighty men of valour, even 10,000 captives, and all the craftsmen and smiths: none remained, save the poorest sort of the people of the land.” It takes little imagination to see his prisoners pressed into forced labour on his megalomaniac construction projects. When he was not having enormous gold images of idols set up for popular worship on pain of death by incineration, the Babylonian king was embellishing his capital with the most opulent buildings.

Mysteriously, Herodotus makes no mention of the Hanging Gardens, one of the ancient seven wonders of the world. Diodorus the Sicilian, the first-century BC Greek historian, said the world’s most famous water feature was born of one man’s love for a woman. “There was likewise a hanging garden … near the citadel, not built by Semiramis, but by a later prince called Cyrus, for the sake of a courtesan, who, being a Persian, they say, by birth and coveting meadows on mountain tops, desired the king by an artificial plantation to imitate the land in Persia.”

Other accounts suggest that these lush, gravity-defying, terraced gardens were a gift from Nebuchadnezzar to his wife Amyitis. Some archaeologists believe they never really existed on the epic scale suggested by legend.

Herodotus writes about all aspects of life in Babylon, covering everything from its general geography, the tradition of brick-baking, the construction of the outer wall and the street plan of the city to the main crops grown (wheat, barley, millet, sesame and dates), the various uses of the palm tree (food, wine and honey), religious, medical and sexual practices and the types of boats used to navigate the Euphrates. He describes how the formidable city walls were built of oven-baked mud bricks laid using hot bitumen for mortar, traces of which can be spotted today where the ancient walls meet the bricks laid in the kitsch, Saddam-era restoration of the 1980s.

One of his tallest stories centres on what he calls the “wholly shameful” practice by which every Babylonian woman, rich and poor alike, is forced to sit outside the temple of Ishtar until a man throws a silver coin into her lap for the right to have sex with her. Only after she has discharged this unpleasant duty is she set free. Herodotus ends the anecdote with a characteristically high-spirited punchline. “Tall, handsome women soon manage to get home again but the ugly ones stay a long time … some of them, indeed, as much as three or four years.”

Babylon’s legacy

The story of Babylon is the ebb and flow of slaughter and mercy, war and peace, a microcosm of human history. It is a tale of greed, hubris, empire and religious persecution; also of human civilisation, prodigious wealth, architectural glory and religious tolerance. It encapsulates humankind’s finest and most deplorable traits, and burst on to the world’s media during the Iraq war precisely because Babylon is the source of our history. The birth of human civilisation belongs to us all.

I visited the site in November 2004, just as Polish troops were preparing to hand it over to the Iraqi authorities. The late Donny George, then head of the Iraq Museum, had warned me in Baghdad about the terrible damage done to the site by the Polish military. He was aghast at reports of soldiers filling sandbags with earth containing archaeological fragments; of armoured vehicles crushing sixth-century BC bricks on the Processional Way; of looters gouging out pieces of dragons from the Ishtar Gate; of digging, levelling, compacting and gravelling in this ancient city. “It’s mankind’s greatest heritage site,” he said. “You don’t just start digging it up to make more room for your tanks.”

Dr John Curtis, keeper of the Department of the Ancient Near East at the British Museum, visited Babylon in late 2004. In his report, he said it was “regrettable” that a large military base should have been established on one of the world’s most important archaeological sites. “This is tantamount to establishing a military camp around the Great Pyramid in Egypt or around Stonehenge in Britain.”

Guided by a Polish civilian with a doctorate in the archaeology of death, I walked through the Ishtar Gate in the sandalled footsteps of both Cyrus the Great and Alexander, who took Babylon in 539 BC and 331 BC respectively – Alexander ordered the famous ziggurat to be levelled and died before it could be reconstructed. The gaudy gate is a replica of the original, carted off by German archaeologists in 1914, together with most of the lions in relief that once decorated the walls of the Processional Way and now stand in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Sections of the Processional Way, having shed their glazed revetment, glowed in the sun like giant teeth decorated with Nebuchadnezzar’s “awful dragons” and bulls. A colony of pigeons landed among the high-walled ruins to rest in the sun and shit all over history.

It was easy to be despondent. While wars routinely shape history, dispose of old powers and bring new ones to the fore, in Babylon war seemed not to have shaped history so much as to have erased it altogether.

Yet this wasn’t entirely true. The Saddam-era restoration, anathema to professional archaeologists, had at least given Iraqis something to look at amid the forlorn mounds, ruins and piles of rubble. As the Iraqi art historian Dr Lamia al Gailani put it: “Ruins in Iraq are ugly for most people. Ordinary Iraqis want something they can be impressed by like this.” And amid this Despot’s Disney, there were historical parallels between Nebuchadnezzar’s boasts in burnt brickwork and those of his 20-century successor (“This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq”).

The truth is that Babylon had long ago been brought to earth, besieged by wars, weather and time. The looting and levelling in 2003 were merely the latest attack on the shrinking fabric of the city, seat of a world-spanning empire which had given its name to denote greatness, untold wealth and ostentation, not to mention decadence and debauchery (the Oxford English Dictionary called it “the mystical city of the Apocalypse”).

Though its most ancient ruins are virtually extinct, through its cycle of destruction and reconstruction and in our collective memory of what it means to be human, Babylon will always endure.