Archaeology reveals the material remains of past lives, exposing who we are and where we come from. Egypt’s colossal pyramids are a spectacular reminder of the ingenuity and know-how of the ancient Egyptians, and we are moved when we see the ashy remains of Pompeii’s citizens who were killed when Mount Vesuvius erupted. When Howard Carter revealed the gold and jewels of Tutankhamun’s tomb, he showed us just how spectacular, lucrative, and informative some archaeological finds could be. Unfortunately, many magnificent archaeological sites have yet to reveal their secrets. This article gives you the scoop on five of the most intriguing and enthralling archaeological mysteries that are still waiting to be solved.

1. Why Is the Location of Alexander the Great’s Tomb One of the World’s Greatest Archaeological Mysteries?

The year is 323 BCE, and Alexander the Great of Macedon is just 32 years old and at the height of his powers. While resting in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon, he falls very ill after a bout of heavy celebratory drinking. After about 11 days of undiagnosed weakness and a loss of consciousness, Alexander dies. It was an inglorious death for such a celebrated and battle-hardened leader.

Alexander’s remains were not allowed to rest. After securing his body in a gold sarcophagus and coffin, his generals and friends organized a colossal procession to take Alexander’s body back home to be buried in Macedon. But they were ambushed! It wasn’t a hostile raiding party but one of their own, a general in Alexander’s army named Ptolemy, who would rule Egypt as Ptolemy I Soter.

Ptolemy kidnapped Alexander’s body, took it back with him to Egypt, and buried it somewhere in the city of Memphis. His son Ptolemy II Philadelphus moved it to the city named after him, Alexandria, on the Mediterranean coast. The tomb soon became a place of pilgrimage, with famous Romans such as Pompey, Julius Caesar, Augustus, Hadrian, and Caligula, making a point to visit while they toured the city.

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription

Thank you!

And there, the tomb stayed for centuries before it disappeared. The last time it was mentioned in antiquity was by the Greek rhetorician Libanius in 390 CE.

Scholars can’t explain why historical texts fail to trace the location of Alexander the Great’s tomb; nonetheless, archaeologists and historians have given us several theories, and some of the more noteworthy are presented here.

Alexandria is slowly sinking into the Mediterranean Sea at a rate of up to 0.25 centimeters each year. Perhaps, thanks to this subsidence, the tomb sank further underground and was then rapidly buried and then built over to support the city’s growing population.

In 391 CE, Emperor Theodosius proclaimed that Christianity was the only legal religion. All symbols of paganism became an abomination. Therefore, it is possible that a mob of righteous and rampaging Christians, aghast at the adoration of Alexander’s tomb, destroyed it in a fit of feverous rage. There is precedence for this theory because Alexandria’s temple of Serapis (the Serapeum) was destroyed in 391 CE, likely by a Christian mob.

Another intriguing possibility is that Alexander’s body, mistaken for that of Christian martyr Saint Mark, was snatched from its tomb and secreted across the Mediterranean Sea to Venice, where it was buried within the Basilica di San Marco (St Mark’s Basilica). If true, this would be one of the greatest cases of mistaken identity on record!

There have been over 140 officially sanctioned excavations to find the tomb, none of which have succeeded. With technological advances such as ground-penetrating radar, who is to say that the next excavation won’t strike it lucky, solving one of the world’s most fascinating archaeological mysteries?

2. Why Hasn’t the Cretan Minoan Linear A Script Been Translated?

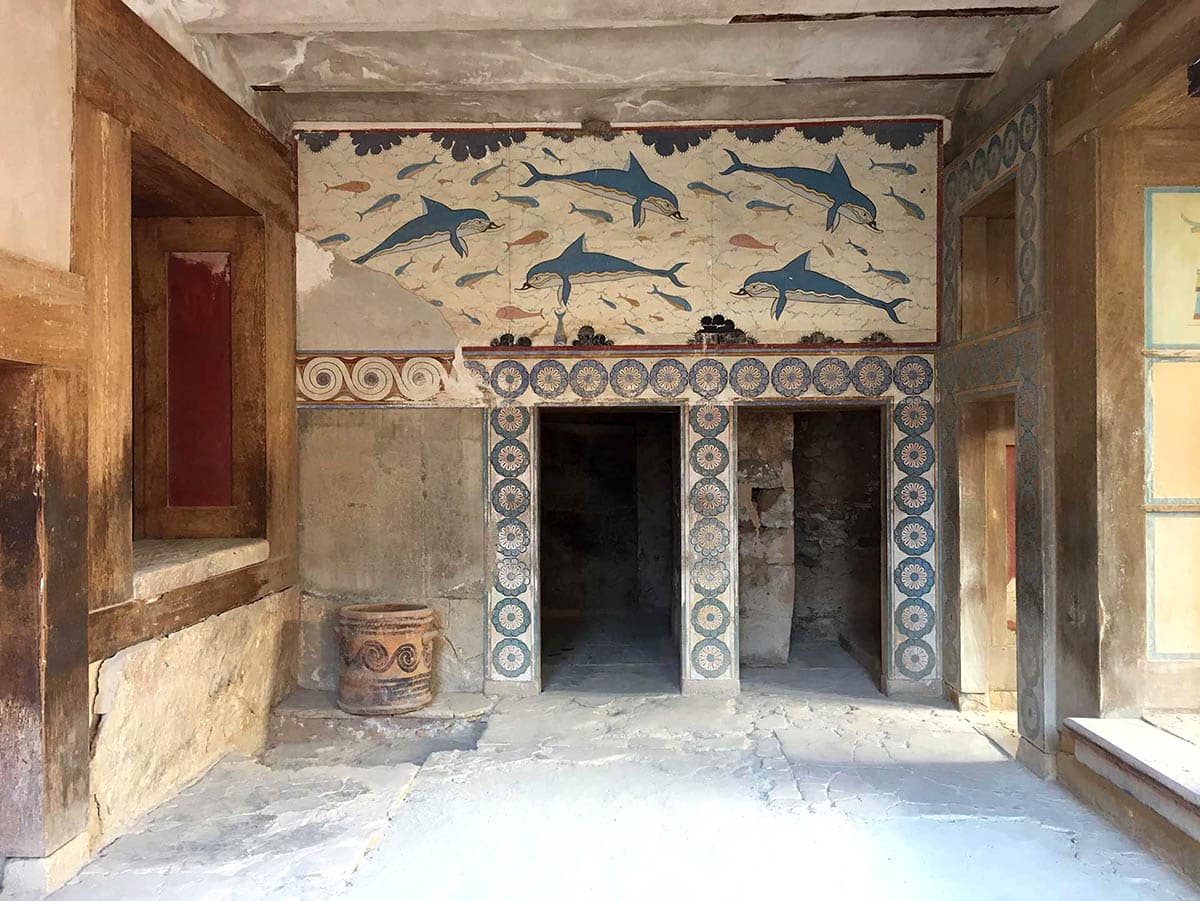

In 1886, British archaeologist Arthur Evans, an expert on Aegean civilizations of the Late Bronze Age, started collecting pottery fragments on Crete that were covered in a mysterious written script. Little did he know that they would remain undeciphered almost 150 years later.

With more examples uncovered during his excavations of the Palace of Knossos that began in 1899, Evans found that script was part of a linear system of writing – as distinct from the pictorial hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt or the cuneiform texts of Mesopotamia – connected to the Minoan civilization that flourished on Crete between around 1800 and 1450 BCE. In Minoan chronology, this was between Middle Minoan IIA and Late Minoan IB.

Evans also discovered another script that he called Linear B, which was deciphered in the early 1950s and turned out to be an early form of Greek used to write the Mycenaean language.

Ancient languages are difficult to decipher, and there are many examples of written texts that have yet to be translated, including the Harappan script of the Indus Valley civilization in Southeast Asia, the Olmec script of the Olmec civilization in Mesoamerica, and the Rongorongo glyphs of Rapa-Nui (Easter Island) in the Pacific, to name just a few.

The lack of a translation of the Linear A script, if not for want of trying, and based on comparisons with the later Linear B Script, which emerged in the archaeological record sometime around 1400 BCE, the texts are probably accounting figures and other record-keeping information. This is logical, considering that the Minoan palaces on Crete most likely acted as storage and redistribution centers for foodstuffs such as barley and wheat.

Recent research by Dr. Ester Salgarella at the University of Cambridge has used linguistic studies, archaeology, and paleography to develop an online database of Linear A signs called SigLA -The Signs of Linear A: a Paleographic Database. It’s as close to a Rosetta Stone for Linear A script that Minoan scholars have.

With the searching capability of an online database that currently lists 300 signs, 400 hand-written inscriptions, and more than 3,000 individual signs, Dr. Salgarella has found that the connection between the scripts for Linear A and Linear B is more subtle than previously thought and that parts of the earlier script were adapted by the Greeks in the Linear B script.

With her work and the processing power of modern computers, scholars are one step closer to understanding one of the enduring archaeological mysteries of the ancient world and unlocking the written word of the ancient Minoan civilization.

3. Why Were the Peruvian Nazca Lines Created?

The Nazca Lines are a collection of massive geoglyphs scattered throughout the Nazca Desert of Southern Peru. They were created by the people of the Nazca culture between 400 BCE and 500 CE, who revealed a layer of distinctive yellow-grey soil by moving large stones and small pebbles scattered throughout the desert landscape.

There are over 800 straight lines, 300 geometric figures, and 70 spectacular animal and plant designs (biomorphs) that make up the corpus of Nazca Lines. Because most are huge–between 400 and 1,100 meters long–the best way to view them is from above, about 500 meters in the air.

The geoglyphs are spectacular in their detail and artistry. The most recognizable are clear representations of animals, including a spider, monkey with a looped tail, hummingbird, condor, pelican, lizard, and whale.

Since their re-discovery by Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejia Xesspe, who spotted them while walking up a hill in 1927, scientists, archaeologists, and anthropologists have debated why the Nazca Lines were created.

One of the earliest theorists was Paul Kosok, the first scholar to view them from the air. He initially suggested that they were part of an ancient irrigation system. Alongside Richard Schaedel and Maria Reiche, Kosok later proposed that the lines may even have been part of astronomical features such as an observatory or astral map. They thought that the lines indicated points on the horizon where the sun and other celestial bodies rose or set during the solstices. However, archaeoastronomers Gerald Hawkins and Anthony Aveni suggest that there is not enough evidence to support this theory, and it is therefore not widely supported.

Johan Reinhard proposed one of the most popular current theories: that the Nazca people created the lines as ritual pathways to guide them to sacred spaces where they could plead to the gods for more water and fertile crops.

In 2011, a Japanese team from Yamagata University discovered two small figures. It was the culmination of five years of fieldwork which revealed 100 new geoglyphs. As recently as 2019, and with the help of machine learning and artificial intelligence, they could scan the data gathered from past research and find previously unrecognized geoglyphs.

With rapidly evolving drone technology and computing power, there’s little doubt that more Nazca geoglyphs will be found. And with them, perhaps more that will allow archaeologists to prove definitively why the Nazca people created them.

4. Why Did the Diquís People Carve the Stone Spheres of Costa Rica?

There are over 300 petrospheres (stone balls) in Diquís Delta and on the Isla del Caño in southern Costa Rica. Known by the locals as Bolas de Piedra, they are believed to have been created by the Diquís culture that flourished in Costa Rica between around 600 and 1500 CE. They range in size from between 70 centimeters and almost 2.57 meters in diameter and are estimated to weigh as many as 16 tons.

Most of the stones are precisely carved from the igneous (volcanic) rock known as gabbro, a coarse version of basalt. There are also over 20 carved from the softer forms of limestone and sandstone.

Most archaeological sites in Costa Rica have suffered from centuries of looting, but the stone spheres were saved thanks to the thick layers of heavy sediment that kept them covered and hidden for hundreds of years. They were discovered in the 1930s when the United Fruit Company cleared large swathes of land for banana plantations in southern Costa Rica. They are now on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites as part of the Precolumbian Chiefdom Settlements with Stone Spheres of the Diquís.

According to John Hoopes, the director of the Global Indigenous Nations Studies program at the University of Kansas,

John is sure, however, that they do not represent the remains of an ancient battle between humans and aliens for control of Earth, as some people have proposed.

5. Why Is Jordan’s Khatt Shebib Wall One of the Most Enduring Archaeological Mysteries?

The Khatt Shebib (Shebib’s wall) is an ancient stone wall that stretches over 150 kilometers through Jordan’s stark desert landscape. It is believed to begin close to Wadi al-Hasa in central Jordan, and it traverses the stony flats and sandy hills towards Ras An-Naqab in the south.

Although locals have known about the wall for centuries, it came to international attention in 1948 when British diplomat Sir Alec Kirkbride noticed the wall as he flew above the landscape. Today, it is being investigated by archaeologists with Aerial Archaeology in Jordan (AAJ). They have found that it runs in a south-southwest to north-northeast direction and has branching walls along its length. There are also around 100 towers that measure between two and four meters in diameter, which were likely used as watch-towers and places where people could shelter from the harsh desert sun.

Archaeologist David Kennedy says that the pottery found along the wall indicates that it was most likely built sometime between the Nabataean Period (312 BCE and 106 CE) and the Umayyad period (661-750 CE). It may have been built at the behest of a local authority or unorganized insular communities.

The wall was only built to about one meter high and about half a meter thick, which means that it wasn’t designed as a defensive barrier. Archaeologists have suggested that it was a secure shelter for hunters and travelers, a hide to make hunting easier, or perhaps even an agricultural barrier between sedentary farmers and nomadic hunters.

Perhaps the wall was some type of boundary with a purpose that has yet to be discovered? With more extensive on-the-ground fieldwork, there is the possibility that the mystery will finally be solved.