The statement ricocheted across newsrooms and social feeds within minutes. What began as a corporate disagreement exploded into an existential crisis for America’s favorite ritual.

“The Super Bowl is not just a game,” one analyst said. “It’s identity.”

When Coca-Cola CEO James Quincey declared publicly, “I will end my sponsorship of the Super Bowl if they let Bad Bunny perform at halftime,” he did more than challenge a booking. He fired an open warning shot into the heart of American pop culture.

For decades, Coke’s red-and-white branding has been woven into the fabric of Super Bowl Sunday. Now, the two most iconic institutions in U.S. consumer life—the NFL and Coca-Cola—stand on opposite sides of a cultural fault line.

The Ultimatum

Quincey’s remarks were not buried in a boardroom memo; they were delivered for maximum visibility. The NFL had just announced Puerto Rican megastar Bad Bunny as the upcoming halftime headliner—a bid for global reach and younger viewers.

To the league, the choice signaled progress. To critics, it symbolized abandonment of tradition.

Within hours, hashtags #BoycottBadBunny and #CokeVsNFL dominated X (formerly Twitter). Fox News cast Quincey as defender of American values; MSNBC framed him as a corporate censor.

The NFL responded tersely: “The Super Bowl halftime show reflects the diversity and dynamism of our audience.” The brevity only deepened speculation that the league had been blindsided.

Bad Bunny: The Flashpoint

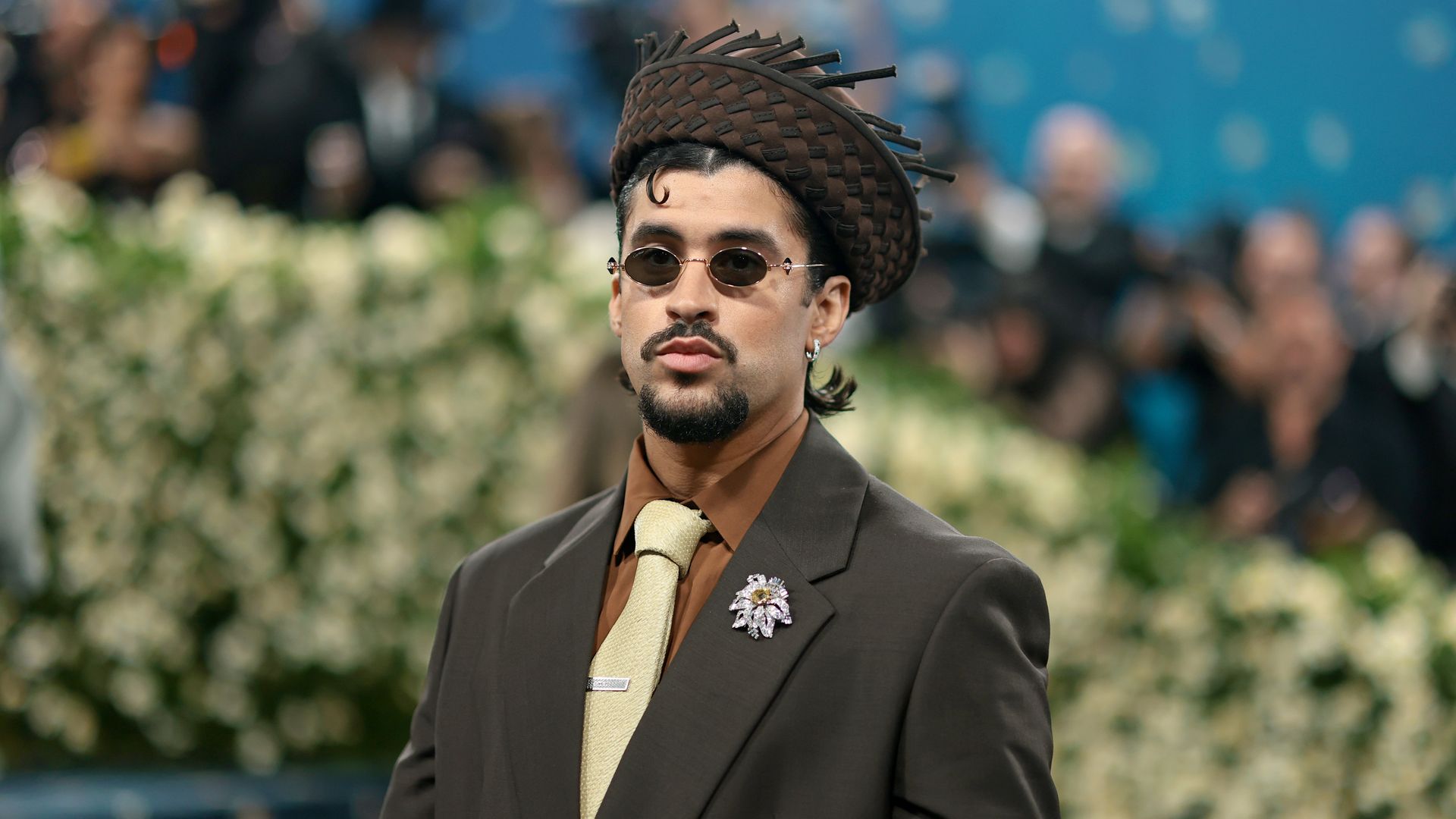

Bad Bunny—born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio—is not simply a pop act. He is a global phenomenon who raps in Spanish while topping English-language charts, challenges gender norms through fashion, and wades unapologetically into politics.

To fans, he’s authenticity incarnate. To detractors, he’s provocation personified. His Super Bowl selection became shorthand for a larger cultural question: Is America’s biggest broadcast still about football—or about reflecting a changing world?

From Michael Jackson’s theatrical 1993 set to Beyoncé’s politically charged 2016 performance, halftime has long been a stage for statement. Bad Bunny was simply the next escalation.

Coke’s Calculus

Why would the CEO of one of the world’s most recognizable brands take such a gamble?

Partly demographics, partly dollars.

Coca-Cola’s core consumer overlaps with the NFL’s traditional base: middle-class, middle-American, family audiences who still watch live TV. For decades, Coke has tethered its identity to Americana—the polar bears, the “Teach the World to Sing” ad, the bottles at every tailgate.

By embracing Bad Bunny, the NFL appeared to chase global and Gen Z markets at the expense of that base. For Quincey, silence risked alienating loyal customers; speaking up risked controversy. He chose the latter.

And financially, the stakes are massive. Coke’s Super Bowl sponsorship costs tens of millions annually. Pulling out would sting the NFL and embolden other sponsors to flex similar leverage.

As one insider put it: “Quincey wasn’t bluffing. He reminded everyone who really pays for the party.”

Fans in the Crossfire

Public reaction split instantly.

In Dallas, talk-radio callers raged that “the NFL forgot who built this sport.” In Los Angeles, younger fans countered that “football needs to evolve.”

A Morning Consult poll captured the divide: 48 percent of NFL fans disapproved of Bad Bunny’s booking; 35 percent approved. Among fans under 30, approval jumped to 61 percent.

The Super Bowl—once a unifying ritual—had become another front in America’s culture wars.

Culture vs. Commerce

The difference this time is who’s wielding pressure. Past halftime controversies—Janet Jackson’s wardrobe malfunction, Beyoncé’s Black Panther imagery—came from fans and politicians. This one comes from a Fortune 500 CEO.

It raises uncomfortable questions: Who decides what America watches—the league, the artists, the audience, or the sponsors footing the bill?

The NFL has long balanced tradition with innovation. By picking Bad Bunny, it leaned global. By threatening to walk, Coke yanked it back toward Americana. The tug-of-war is now public, visible, and destabilizing.

A History of Halftime Flashpoints

-

1993 – Michael Jackson: too theatrical for purists.

-

2004 – Janet Jackson: wardrobe malfunction prompts FCC fines.

-

2012 – M.I.A.: a single middle finger sparks lawsuits.

-

2016 – Beyoncé: political imagery angers police unions.

The NFL survived them all. What’s new is scale: no sponsor of Coke’s stature has ever threatened to pull out, potentially fracturing the economics that keep the spectacle running.

Inside the NFL’s Crisis Meetings

Sources say the league is holding daily calls with top sponsors. Some, wary of alienating traditional consumers, sympathize with Coke. Others—Nike, Pepsi—support the Bad Bunny gamble, seeing it as aligning with global youth culture.

Commissioner Roger Goodell faces an impossible equation: Stand firm and risk losing a legacy partner, or capitulate and alienate a generation of future fans.

Stakes Beyond Football

If Coca-Cola succeeds, sponsors everywhere may feel emboldened to dictate cultural content. If the NFL resists, it accelerates a generational pivot away from tradition toward globalism.

And for Bad Bunny, controversy is currency. Whether he performs or not, he’s already become part of Super Bowl mythology.

Possible Compromises

Insiders whisper about a middle path: keep Bad Bunny but pair him with an Americana counterweight—Garth Brooks, Bruce Springsteen, maybe even Taylor Swift—to temper backlash. Whether such a pairing would satisfy either camp remains doubtful.

Production timelines leave little room for delay. The NFL has mere weeks to finalize its decision.

The Soul of the Super Bowl

In the end, this fight isn’t just about music. It’s about the soul of the Super Bowl—and by extension, the identity of American culture.

For decades, the game has mirrored the nation’s contradictions: unity and division, commerce and creativity, patriotism and pop. Quincey’s ultimatum merely forced those tensions into the open.

When the lights rise on February’s halftime stage, the world will watch more than a performance. It will watch the outcome of a corporate and cultural power struggle that could redefine both sport and spectacle.

The question lingering over the field is simple—and seismic:

Did the NFL protect its tradition, or gamble it away?